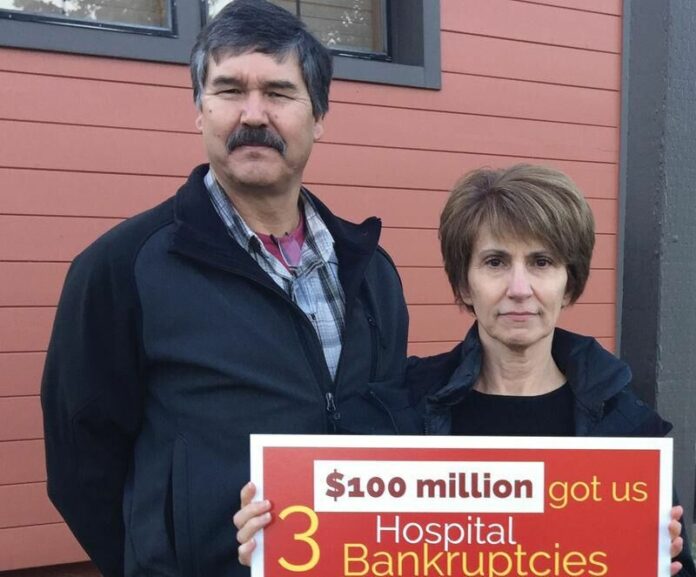

It’s hard to believe this past year could possibly contain the epic zigzags of the Palm Drive Health Care District (PDHCD), and it doesn’t. But the beginning of the end began not more than 48 hours into 2020, when Jim Horn, Gayle Bergmann and Alan Murakami formally notified Sonoma Local Agency Formation Commission (LAFCO) they would petition to dissolve the district.

The essential argument for turning off the lights was that the district used parcel tax funds for missions other than what voters approved when they passed the two levies, Measure W in 2004, in particular, to power PDHCD after its inception in 2000 to maintain Palm Drive Hospital and its emergency room in Sebastopol.

PDHCD sold what was once Palm Drive Hospital to the private company American Advanced Management Group (AAMG) as a long-term acute care facility in 2019, with taxpayers still forking over $300,000 to $500,000 a year to pay salaries and legal and accounting costs, Sonoma West Times & News reported in January.

The taxes draw $155 from landowners within the district and about $105 from landowners in detached zones in perpetuity, which Bergmann called attention to.

Measure W states “the primary purpose of the measure is to ensure that Palm Drive Hospital, with its Emergency Room serving approximately 10,000 patients yearly, can remain open,” but some district representatives wanted the district to keep funding the “other medical and physician services,” mentioned in the measure’s text, like the Gravenstein Health Action Chapter.

As one of Sonoma County’s nine Health Action chapters, the organization backed preventative public health services in Sebastopol, Occidental, Bodega, Bodega Bay and Graton, according to later reporting by Sonoma West Times & News.

The PDHCD board actually received a legal opinion on Measure W’s language from the Hanson Bridgett law firm in January, but PDHCD attorney William Arnone said the board claimed attorney-client privilege and sought an alternative report from the firm for the public.

Former board member and petition-canvasser Horn filed a California Public Records Request for the opinion.

On Feb. 3 Board President Dennis Colthurst motioned for a resolution to dissolve the district, ideally by June 30, 2020. Other board members acknowledged the long-drawn efforts and agreed with the decision.

LAFCO Director Mark Bramfitt said PDHCD could dissolve through a vote of either the county board of supervisors or the LAFCO board, a citizen petition or district board resolution. Whatever happens, he said taxpayers would still have to see the district’s debts through with their parcel taxes.

Previously, district treasurer Gail Thomas said it would take 10 to 15 years for landowners to pay off the district’s $28 million bankruptcy and bond debts, Sonoma West Times & News reported in January.

Murakami said the petition already had over 1,200 of the 2,400 registered voter signatures needed in the first of the six months of the campaign.

That February, Arnone said the Hanson Bridgett law firm not only refused to write a separate public summary of its legal opinion on Measure W, but planned to formally recommend the board withhold the report from the public.

Sonoma West Times & News also reported in February the impending dissolution of the district could spell the end for the Gravenstein Health Action Chapter. The chapter’s financing through Measure W frustrated community members who wanted funds directed only to the hospital itself.

Its steering committee was also a PDHCD subcommittee of director Alanna Brogan, Eira Klich-Heartt and Gail Thomas of the board and other residents with Brogan holding a paid position.

As of March, LAFCO’s vote to dissolve the district was set for July 1 and the PDHCD board tentatively planned for official dissolution by July 15. The district’s plan to vote on the dissolution resolution and application May 4 and turn both in to LAFCO May 5 wasn’t welcomed by opponents who preferred the district resolve to dissolve first and prepare the application after, arguing the sooner the district dissolved, the sooner the district would stop spending money on community health programs.

Former board member Horn said the board earmarking $200,000 for community services in the next fiscal year didn’t make sense since the county would assume the district’s assets by then and direct them to covering debts.

In April, PDHCD attorney Bill Adams told the board and community members gathered over Zoom that he and Brogan received an email from Auditor-Controller-Treasurer-Tax Collector Erick Roeser when the shelter-in-place order began that the COVID-19 emergency response would delay the county’s adoption of the district’s finances until autumn.

Uncertainty arose whether the district could dissolve soon enough to avoid paying thousands of dollars for the November election when some board positions would otherwise open up.

LAFCO Director Bramfitt said the district may be overcomplicating its dissolution application when the county ultimately takes control.

Meanwhile, Sonoma West Times & News reported taxpayers continued to pay $3 million in levies toward the $28 million debt, followed by district staff and lawyer salaries and the thousands the district continued to spend through the Gravenstein Health Action Chapter on health care program grants.

By May, the PDHCD board marked the calendar to dissolve by the end of October, right before the Nov. 3 election because of the county’s delay, as the district’s lawyers said the district would probably need to pay for the election.

Deva Marie Proto of the Registrar of Voters said running a vote to fill three opening board seats would cost around $75,000 to $125,000.

Finally, the board voted unanimously on May 12 to dissolve the district by July 1 and hand their dissolution application to LAFCO, under pressure of potentially paying dearly for a pointless election and PDHCD attorneys suggesting dissolution could drag out into 2021, Sonoma West reported.

June was one more can of worms for the PDHCD board and the community when it was reported that PDHCD lawyer Adams stated LAFCO forgot to notify state agencies that the district would be dissolving.

Bramfitt said no, LAFCO had indeed informed all four state entities as needed. The district’s dissolution would inevitably be delayed again because while the board planned to wrap things up in one month, state agencies had 60 days once Bramfitt notified them at the end of May.

Luckily, Proto of the Registrar of Voters said the district didn’t need to file for a November ballot if they didn’t anticipate the PDHCD would exist by then, saving the district at least $75,000, according to Adams.

Sonoma West Times & News reported that the public largely came to the early June meeting to hear the board’s decisions on the 2021 tax rate and the Gravenstein Health Action Chapter, but the items “had been removed from the agenda during a 5-minute open session earlier in that day, when no members of the public were present.”

County assessor Roeser ultimately requested the district’s ad hoc committee come up with a two-rate structure for taxpayers to pay off the debts.

As for the Gravenstein Health Action Chapter, Roeser informed board president Colthurst and executive director Brogan that his office didn’t know if the parcel tax funds could actually cover the district’s debt and requested the district not grant funds until he could ascertain they could afford it, and “promised to claw back any money the district granted to another organization should the need arise.”

Yet, Brogan still proposed financing Gravenstein Health Action’s relaunch as the nonprofit Gravenstein Health Action Coalition mid-June. The board voted 3-2 to give its community health subcommittee $200,000, with Randy Coffman and Richard Power in opposition.

Sonoma West Times & News reported Brogan informed the board that the subcommittee applied to become a nonprofit with the state and federal government beforehand and expected state approval for a bank account earlier than the district’s own end date.

But board member Power said, “I have read the Hanson-Bridgett report…and I think it tells us that we cannot fund this proposal.”

Attorney Adams, said the board would deliver a notice of default to AAMG for shutting down the hospital’s urgent care in the spring of the pandemic after agreeing to keep one open for a decade in a $1.2 million promissory note. He also announced the board would release the Hanson Bridgett legal opinion on Measure W at the county’s will after the district discontinued.

After postponing a full month, LAFCO ultimately caught the can kicked down the road and crumpled it up, unanimously voting Aug. 5 to dissolve the district. The county now bears the responsibility of the district’s financial remains — “the district’s assets, liabilities, debts, records and taxing authority” — and decisions like whether to come knocking for the $200,000 the district tossed to the Gravenstein Health Action Coalition or the $1.2 million from AAMG for possibly breaching its $1.2 million promissory note with the district.

Board member Power said the county now possesses the Hanson Bridgett legal opinion on Measure W, at that time still locked away from public view.