Since World War II, women have served their country in times of war. And yet according to local veterans, the United States still has a long way to go when it comes to recognizing women in the military.

The first step towards recognition is awareness. And many people still automatically assume military service members to be men — an assumption that National Guard member and Army veteran Patricia Lay experienced firsthand on a recent National Guard training trip.

“I flew in. I have all kinds of gear, but I was loading up my car at the airport and I swung a duffel bag on my back. I had two other bags in the car and there had been a group of businessmen, well-dressed men … The one gentleman stopped and looked and said ‘Shouldn’t the soldier be carrying that?’” Lay recalled.

“I looked in his eyes and said ‘I am the soldier.’ And the look of surprise on his face just astonished me. This actually surprised me because there are so many women in the service … I’m just surprised that people are still so surprised.”

Lay served as an Army mechanic — a field largely dominated by men — in the 1980s, and joined the National Guard in 2007.

“I would say in a couple of units of 100 people there were probably 10 women that were actually on the line, meaning not office personnel, where there was more women. I think there were only three of us in maintenance at the time,” Lay said.

“It was basically a little bit frustrating and a struggle, even with the equal opportunity and everything … Mechanics isn’t where you’d find a lot of women. I know it was frustrating for leadership to try and make certain arrangements for us as women in a unit of men. It was more in the field environment, when everybody’s living in tents and moving around in the rains and on convoys and us trying to use the restroom and it could be difficult, but we made it work.”

Interestingly, the women that paved the way for today’s female service members — those women who volunteered to serve in World War II — recall similar frustrations.

“Until World War II, women had not done a lot of things that women did in World War II. We opened the door,” said Windsor resident and Navy WAVES (Women Accepted for Voluntary Emergency Service) veteran Bettie Crandall.

“But it was very difficult, because some of the men resented us, because they did not want to go fight, they would rather have kept their old jobs. Women in World War II packed parachutes and ferried airplanes and did a lot of things that women had never done before … but some of the men resented us. The guys would sing, ‘The WACS WAYS will win the war, so what the heck are we fighting for.’”

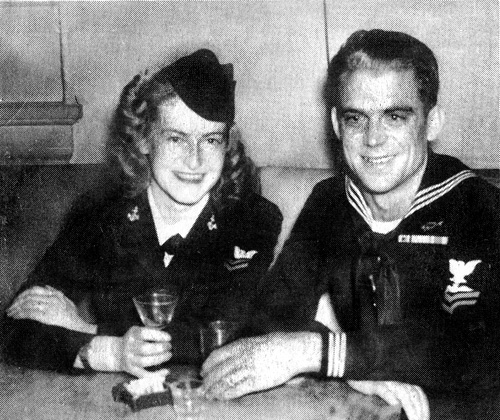

And yet despite the difficulties, many women — including Crandall — signed up to serve the moment they turned 20, and their time in the military shaped the course of their lives. Crandall met her husband while serving. She and Ed Crandall were married for 60 years before he passed away six years ago.

“He was in the Navy, I wouldn’t have married anybody else,” she said. “He stayed in to retire, so we lived in a lot of places.”

Marjorie Barnard was also a member of the Navy WAVES, and she also joined the moment she was able: when she turned 20 in December of 1944. Today, the doorbell of her Healdsburg home chimes with a measure of “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

“You’re supposed to stand at attention for five minutes,” she said of her doorbell, and smiled.

Barnard’s experience was similar to Crandall’s in that the first step was a trip across the country to the Big Apple.

“First of all, you went to boot camp in the Bronx in New York,” Barnard said.

After boot camp, Barnard ended up at a naval air base in Coronado, San Diego.

“When I first got there, I was one of the people they always kid about ‘captain of the head,’ and the head of course is the john. But what I did most was run the big buffers for polishing the floors. Every once in a while they’d lose control and bang into a locker or something,” Barnard said.

An officer decided she needed a better job and before she knew it, Barnard was in the aeronautical chart room, compiling maps that would sit in pilots’ laps and guide them safely from airport to airport.

On the other side of the country, Crandall also rose quickly to a specialized position. After training, she ended up in New York State in the accounting office of the supply department, where she filled requisitions and orders.

“I joined the Navy to see the world and ended up in a state next door, because I grew up in Vermont,” Crandall said, chuckling.

Both women noted that while most of the men they worked with were gentlemen, there were always a few bad apples. And there was always a certain attitude prevalent towards women.

“They used to call the poor Marines women BAMs, meaning broad-assed Marines. A lot of men called them that, I don’t know what they called us,” Barnard recalled. “But the work was good and the sailors, the majority of the sailors, treated you well. There were a few duds as always, but the sailors appreciated you.”

She remembered a certain chief who gave her a hard time — what would, as she put it, possibly be described as “sexual harassment” today.

“I finally told him he was disgusting and so he left me alone,” Barnard said.

Women still face inequality in the military. Healdsburg veteran Lorraine Plass noted that — some seven decades after women began serving — the military has yet to produce boots designed for women’s feet, or bulletproof vests designed to fit women’s chests.

“Women veterans are out there and doing just as tough jobs as men are. There’s a lot of women that are in jobs and end up doing combat no matter what, doing the same jobs that the men are,” Lay said. “Don’t be surprised. Respect us. Don’t think that we’re not giving 100 percent like the guys are.”