In November 2016, Sebastopol lawyer, Omar Figueroa, told me that Proposition 64, which had just been approved by California voters, was “a travesty of marijuana legalization.”

I didn’t believe him, but the last two years have mostly proven him right.

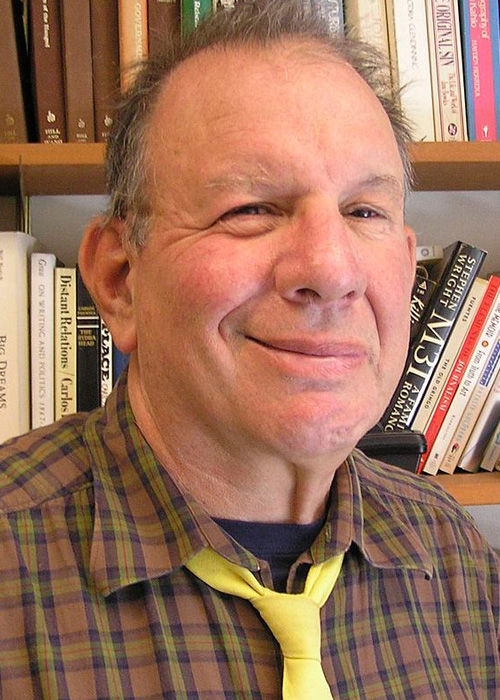

Born in Mexico in 1971, Figueroa came to the U.S. in 1980, graduated from Yale and Stanford Law. He’s been a crusading lawyer for decades.

In one significant way, Figueroa has proved to be off base. As a result of Prop 64, felony arrests for marijuana in California have dropped 56 percent. In the U.S., where marijuana is now legal in some form in 30 states, arrests for cannabis are down about 25 percent from what they were in the peak year of 2011, when 873,000 Americans were busted for marijuana offenses.

Despite “legalization,” it’s still a crime for a Sonoma County resident to possess more than one ounce of marijuana, cultivate more than six plants and provide cannabis to a minor.

It’s not surprising that Figueroa has expanded his office. He has hired two attorneys, Lauren Mendelsohn and Stacy Hostetter, who handle legal issues that pertain to permitting, licensing, regulatory compliance, corporate transactions and more. Figueroa does some of that along with criminal defense work that has made him notoriously famous.

At El Molino Central, his favorite Mexican restaurant, Figueroa talked about his new book, “California Cannabis Laws: MAUCRSA Edition,” that has all the information a lawyer could possibly want about marijuana and the law, a subject that’s often bewildering.

The book ought to be required reading for all five Sonoma County supervisors, who are often in a fog when it comes to marijuana matters.

Lynda Hopkins, the most enlightened of our supervisors when it comes to marijuana, noted recently apropos the transportation of cannabis, “It’s a crazy quilt.”

“California Cannabis Laws: MAUCRSA Edition” is a pioneering work. The word MAUCRSA in the title is the acronym for “Medicinal and Adult-Use Cannabis Regulation and Safety Act,” aka Prop 64.

The book is aimed at attorneys who have to wade through a tangled maze of rules and regulations, and then figure out how to defend clients who are arrested, in jail or facing a long and expensive trial.

“It sometimes seems like cannabis law was intentionally meant to be difficult to comprehend,” Figueroa said. He added, “It’s more complicated than any other area of the law and covers business, health and safety, revenue, taxation, water codes and more.”

Figueroa divided his book into 20 chapters, with titles such as “Enforcement,” “Licensing” and “Delivery,” plus “Fish and Game Code Sections,” and “Labor Code Sections.” You need a lawyer to comprehend the organization of the book.

“It was a labor of love,” Figueroa said in-between bites of a carnitas taco. “I have had compliments from lawyers who say that the book has helped them.”

It’s in the law library at Stanford, Figueroa’s alma mater, and a valuable resource for law students.

After the book was published, Figueroa wanted to promote it on Facebook. He was told “no” on the grounds that it “promoted illegal drug use.” Figueroa pointed out that his book includes all the penalties for illegal drug use. Facebook relented and information about California cannabis laws is now online.

“There will continue to be a cannabis diaspora from Sonoma,” he said. “In Santa Barbara and Monterey, the industry is booming. There aren’t as many NIMBYs there as there are here.”

Figueroa understands some of the complaints. “I wouldn’t want to live next to a big winery or a marijuana manufacturing center either,” he said.

Several predictions that he made in June 2018 came true in July. Dispensaries held fire sales to get rid of inventories.

According to the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML), dispensaries were forced to dispose of 180,000 pounds of cannabis and then struggled to stock shelves with tested and approved products. California’s regulations for testing, labeling, and packaging cannabis, which went into effect July 1, created havoc in the industry.

Soon after meeting Figueroa, I attended a session between a dozen savvy cannabis activists and Sonoma County supervisor Lynda Hopkins, who listened carefully and took detailed notes. A can-do-elected-official, Hopkins is always ready to roll up her sleeves and tackle the big issues with integrity.

But I came away from the session with the unmistakable feeling that the attempts to regulate and tax cannabis in the county have been and still are largely an abject failure.

A year ago, I sensed that the county was in trouble when Tim Ricard was appointed the manager of the cannabis program. “It’s not a big deal to go through the permitting process,” he told me. A year later, it has turned out to be a very big deal, indeed.

Sonoma County might consider giving up its brave experiment in regulating and taxing cannabis. The waste of taxpayer money, the political corruption and the breakdown in trust between local government and local citizens provides more than enough reason for Hopkins and the other supervisors to wave a white flag and say, “We tried. We didn’t succeed. Let’s move on.” Either that or make radical changes in the ways the county handles cannabis.

Jonah Raskin, a professor emeritus at Sonoma State University, is the author of “Marijuana: Dispatches from an American War,” published in French as well as English, and shares story credit for the feature length pot film Homegrown. His monthly column, “Cannabis Country” is now two years old.