This and other hard questions abound in the high school district’s budget committee report

At the last West Sonoma County Union High School District (WSCUHSD) board meeting on Dec. 18, Superintendent Toni Beal gave a long-awaited update on the work of the superintendent’s budget committee, which was created in March of this year as part of the district’s fiscal recovery plan. The County Office of Education required the district to create a fiscal recovery plan because the district’s three-year financial projections show year three in the red by more than $700,000.

The budget committee includes the superintendent; principals from El Molino, Analy and Laguna; as well as teachers, parents and representatives of the classified staff. Chief business officer Mary Schafer was a member of the committee before she left her position in December.

The purpose of the budget committee is to look at a range of possible solutions for the budget deficit, including the following:

1) Cutting the district’s ballooning services budget;

2) Cutting 7th period;

3) Changing state funding from LCFF to Basic Aid;

4) Consolidation with nearby school districts into a larger district;

5) Consolidating school campuses (long the elephant in the room). In this case, “consolidating” means closing one or more of the district’s high school campuses.

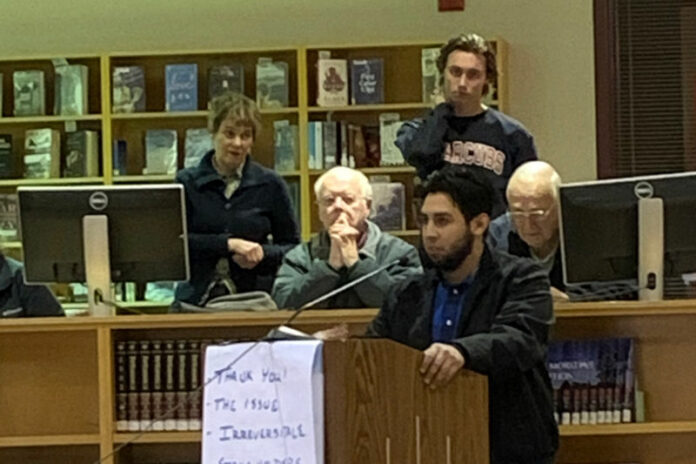

The library at El Molino where the board meeting was held was crowded with people who’d come to speak against one of those options, which the district was considering implementing as soon as next month: a plan to save $217,168 by moving Laguna High School, the district’s continuation school, to El Molino in Forestville.

The meeting began with the passing of the gavel from last year’s board president, Diane Landry, to this year’s board president, Jeanne Fernandes, who started the meeting on a defensive note.

“I want you to know we have not made any decisions. No decisions will be made tonight. This is just a discussion item on our agenda,” Fernandes said. “We do want to hear what you have to say, and we would appreciate not being attacked. We do have a responsibility to hear all of these items and to discuss them.”

Beal then presented the various options explored in the report:

Cutting the services line item down to size

Throughout the last year, teachers union representatives often pointed to the district’s bloated services budget, noting that it was about 25% higher than similar schools.

The budget committee considered two items in the service budget: transportation and special education.

Transportation. Earlier this year, the district changed bus routes for El Molino, shortening several routes in far west county, including Cazadero and Fort Ross. What they found was that doing so meant that several students were unable to regularly make it to school, which cost the students learning time and cost the district ADA (average daily attendance) funds. They are considering reinstating these routes and cutting Analy bus routes instead, since Sebastopol students have the option of free public transit using the bus system in the town.

Special education. The district spends hundreds of thousands of dollars every year paying for special public or private education for special needs students. Beal said a new program would serve those students within the district and perhaps even make money by serving special education students from other districts.

The six period day (otherwise known as cutting 7th period)

Although agreeing not to cut 7th period this year was a part of the district’s agreement with the teachers union this fall, this option is still on the table for next year. The district initially estimated that this would save $600,000 in one fell swoop. Analysis by the budget committee took into account the number of students who might leave the district if 7th period disappeared and revised that savings down to $300,000.

Changing from LCFF to Basic Aid

In the acronym-ridden world of public education, LCFF is short for Local Control Funding Formula and is primarily based on ADA. In general this means that the more students a district has — and the more regularly they attend school — the more money a district gets from the state.

This is not the only funding option in California, however. A few schools in Sonoma County operate on what’s known as Basic Aid. These schools are not funded based on student population and attendance, but from local tax revenues.

Small schools in wealthy areas can often get more money per pupil this way. Basic Aid creates the opposite incentive structure from LCFF. Instead of encouraging districts to poach students from surrounding districts to boost their own numbers, Basic Aid districts generally disallow intradistrict transfers because that would mean having to divide the financial pie into smaller pieces.

The budget committee explored a four-year plan to move all out-of-district students out of WSCUHSD. This would drop the student population of the district from its current 1,760 students (as of Sept. 2019) to just 947 students, with a corresponding drop in the number of the teachers.

“That will be a pretty tumultuous process for the district,” Beal said. “It would be a continual cut of students and staff over a period of four years.”

It would also likely trigger the closure of Analy or El Molino.

Campus consolidation in long term

Beal outlined the longterm options for campus consolidation.

“The suggestions included Analy moving to the El Molino campus, El Molino moving to the Analy campus, the district office moving to one of the campuses and Laguna moving to the El Molino campus,” she said.

“Moving one of the comprehensive high school populations to one of the other high school campuses would obviously be a multi-year process,” she said, “because neither of the school sites currently have enough room to place all the students from the other high school on its campus. So at this time, we have not researched in depth the feasibility or timeline for either of those things happening.”

Campus consolidation in the short term: Should Laguna High School be moved to El Molino?

Meanwhile, a real and immediate campus consolidation was on the table: namely should Laguna High School, the district’s continuation school, be moved to the El Molino campus?

On paper, the answer seems obvious. El Molino has plenty of room: the school, which was built to hold over a thousand students, only has 546 students (as of Sept. 2019). It has plenty of empty buildings.

The district estimated that cuts to personnel associated with this consolidation — the loss of a custodian, an office secretary, a guidance counselor and one principal — would save the district over $217,168.

A long line of past and present Laguna teachers and students stood up to protest the move, arguing that the needs of Laguna’s vulnerable population of at-risk students could not be served at El Molino.

“If we dissolve our school and move to another campus, we will no longer be able to serve the at-risk youth of our community with the attention, dedication and full range of services that we currently provide,” said Laguna teacher Giana dePersiis Vona. “We need a site principal whose only job is to keep our school running and to meet the ever-changing and ever-challenging needs of our kids. We need a full time counselor who is exclusively dedicated to the incredibly complicated and time-consuming job of making sure our kids have the credits they need to graduate. We need the pride that comes with having our own campus where our students can be reminded every day that they are not less than anyone else, that they are just as smart and just as important as any other student out there.”

Vona, like many of the other speakers, broke down during her presentation and continued through tears.

“Let us not pretend that moving Laguna will be anything less than the death of our school,” she said. “Can a new program be created on the El Molino campus? Of course. Will it ever be able to provide what Laguna High School has provided for the struggling youth in this county for the last 50 years? Not a chance. To even propose such a move demonstrates a total lack of understanding of our student population.”

Numerous students stood up to speak as well. Several mentioned that Laguna is more like a family than just a school and that Laguna saved them from the troubled paths they were on before arriving at the school.

“I was this close to becoming another statistic,” Julio de Santos, a former student, said. “But at Laguna, I felt supported. I felt safe, and I felt like I was home. And by deciding to shut down Laguna, I just want to tell you what that will do: We will be giving up on kids who need us most. And we will be evicting these kids from their home, and some of these kids don’t have another home to go to.”

Lily Smedshammer, president of the West Sonoma County Teachers Association, pleaded with the district to give teachers, students and the public a bit of rest from the drama that has characterized the last year.

Board member Kellie Noe sympathized with Smedshammer’s sentiments but reminded the assembled group that the district still had a $500,000 hole to fill. She invited the public to work with the board in a spirit of “cooperative brainstorming.”

The question of moving Laguna to the El Molino campus will be back on the agenda at the school board’s next meeting on Wednesday, Jan. 22 at 6 p.m. at the library El Molino High School.

To read the complete superintendent’s budget committee report, see the sidebar.