Modeling data from the Imperial College of London reveals that Sonoma County’s shelter-in-place order is significantly flattening the curve of COVID-19, and reducing the mortality rate for those over the age of 65. In doing so, the curve is also being stretched out, meaning the surge in cases will likely occur in about 60 days, requiring about 1,500 hospital beds.

Without a shelter-in-place order, Sonoma County Public Health Officer Dr. Sundari Mase said a surge in cases would have peaked much sooner rather than later, and would have required over 9,000 hospital beds, putting a strain on the county’s health care capacity.

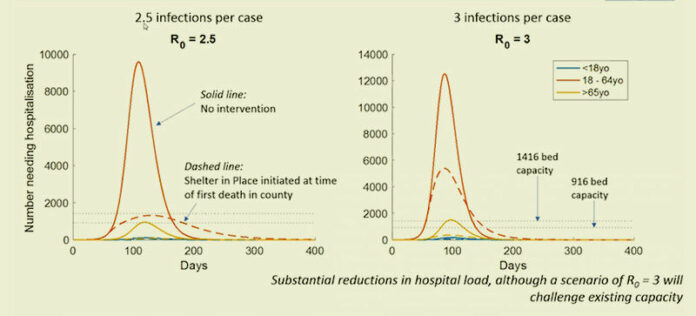

Mase presented two different scenarios based on the R0 (pronounced R-naught) or reproduction rate of the virus. An R0 of 2.5 assumes that every person who currently has COVID-10 will infect 2.5 people. An R0 of 3 assumes that every person who currently has COVID-10 will infect 3 people. Mase said the 2.5 infection rate is probably the more likely scenario.

Mase then explained the assumptions behind the data.

“The first assumption is an estimate of the number of likely new infections resulting from one case,” Mase explained during an April 2 county virtual press conference. “Studies show that the ‘R-naught’ is likely between two or three … We also looked at three age groups: the less than 18-year-old population, the 18 to 64-year-old population and those who are 65 and older. Other assumptions made are the number of people who have COVID-19 who would require hospitalization and the case fatality rate.”

The case fatality rate is the proportion of deaths from the disease compared to the total number of people diagnosed with it.

“These proportions come from published data,” Mase said. “The other assumptions that are made are about symptomatic infections — we’ve assumed that two-thirds of infected patients develop symptoms, the other one-third are asymptomatic and that symptomatic patients are 50% more infectious than asymptomatic.”

In terms of demographic assumptions for the data, the assumption is that 70% of the county population is urban and that the remainder is rural, the age distribution is the same for both, and the rate of infection for rural settings is three-fourths that of urban settings.

With that in mind, Mase explained the graph of data results.

The timeframe of the 2.5 model runs from 0 to 400 days (a little more than 13 months). Sonoma County’s shelter-in-place order was put into effect at about day 50, at a time when the county had about four known cases and one death.

Based on the data and the assumptions used, with the shelter in place, cases will peak about 60 days from April 2, roughly the end of May, when Sonoma County will need about 1,500 hospital beds for COVID-19 hospitalizations. (On the graph, this is represented by the dashed line.)

The graph also show what would’ve happened with the surge in cases had there been no shelter-in-place order, and the difference is staggering. Instead of flattening, the curve spikes sharply, with a much higher number of cases occurring over a shorter period of time.

While the surge would occur earlier, it would require 9,000 hospital beds for patients — a number that would swamp our existing health care resources.

“We are seeing that putting the shelter-in-place order earlier, in terms of the number of cases, is more effective in flattening the curve,” Mase pointed out. “We are better off than places where they started (a shelter in place) later.”

If the shelter order hadn’t been implemented, it is estimated that the mortality rate for those over 65 would be at 0.8% — that is 0.8% of people in the general population over age 65 would die. With shelter in place, the mortality rate for people over the age of 65 is currently estimated to be 0.25%.

Note that the mortality rate is a general population rate. That is different from the case fatality rate—which is the percentage of people who contract the disease who will die from it. Because we are so early in the epidemic, that number is difficult to pin down; however a recent CDC study puts that number between 0.8 and 3.4%.

What happens if the shelter order is lifted?

Mase cautioned that a secondary wave of cases could hit if the shelter-in-place is lifted without additional mitigation measures in place.

“If shelter-in-place is lifted after 480 days, then we would again see a blip in infections requiring 3,000 hospitalizations,” Mase said. “Without further mitigations, the secondary wave could again threaten our health care capacity,” she said.

“The implication is not that we need extended shelter in place, but rather that we really need additional mitigation measures,” Mase said. “Additional mitigation measures would mean things like our parks closures, the closures of our schools, the intensive contact tracing around cases to find new cases and isolation of cases. The ultimate mitigation measure would be a vaccine.”

Mase said a vaccine was probably about a year to a year and half in the future.

Next steps

She said the county will continue to share additional information with the community even when it is preliminary and that this was just the first phase of the modeling project. The county will continue to get more data for future phases of modeling from Imperial College to further inform intervention practices, according to the key messages report from the county.

The next steps are to create more models to see how the curve could be flattened with the following mitigation measures and to work towards a gradual and staged shelter order lift, which could start with businesses and end with schools.

Mitigation measures include the following:

• Increase testing to find secondary cases, contact tracing, strict isolation of cases and strict quarantine of contacts.

• Look at mask guidelines for health care workers, first responders and for the general population. (Since the time of this press conference on April 2, Mase and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have recommended that people to wear masks when going out in public).

When would shelter restrictions be lifted?

Mase said the answer to this question will depend on the county’s mitigation strategies and how effective they are.

“For example, intensive case isolation, contact tracing to find secondary cases and isolate them and following contacts closely to find out if they are symptomatic as quickly as possible so that we can diagnose, as well as some of the other mitigation strategies,” Mase said.

She said they have asked the modeling team to take these mitigation strategies that the county is starting and see how those measures would impact flattening the curve.

“My answer is that we are going to know more soon from our modeling data.”