Jana Adams, a Sonoma County real estate broker, has an extensive support group. She needs it and so does her daughter, Brooke, who just turned 6, and who has Dravet Syndrome, a rare form of epilepsy that typically begins in infancy or early childhood and that’s characterized by seizures that can last minutes or hours. The name for the syndrome comes from Charlotte Dravet, a French doctor who discovered the gene mutation that was later named after her.

Brooke was diagnosed with Dravet Syndrome when she was nine months old. She had her first seizure on September 24, 2013, when she was just three months. Adams said it helped to attach a name to Brooke’s condition, but the conventional medicines that doctors prescribed didn’t help. In fact, many times they made matters worse. On one occasion, when a seizure lasted three hours, Brooke was hospitalized.

To cope with her medical condition, which is genetic, Adams created a support group that includes her parents, her husband, Jon, who works to support the family, and their three children, Luke, who is the oldest, Max, the middle child, and Faith, the youngest, who enjoys spending time with Brooke and helps care for her.

Luke went to Sacramento on “Lobby Day” to call for legalization of medical cannabis on school campuses, like other medications used by students.

“It takes a village,” Adams tells me in her office in Santa Rosa at Northern Nest, where she is the president of the company she founded in 2015.

The support system that Adams created where none previous existed has five crucial individuals in addition to her biological family members; Sarah Shrader, a cannabis activist with Americans for Safe Access; marijuana attorney Joe Rogoway; two doctors, Bonni Goldstein, the author of Cannabis Revealed, and Joseph Sullivan, a Dravet specialist at UCSF; and Jason David, the owner of Jayden Journey, a cannabis dispensary in Modesto.

Adams drives to Modesto, buys medicine for her daughter and drives back to Santa Rosa. It’s against federal law to send THC through the mail. Also, Brooke can’t fly on an airplane because it’s illegal to transport THC; she has to have her medicine with her at all times.

Adams praises Dr. Goldstein because she explains how medical cannabis works in the human body — which has natural cannabinoid receptors and endocannabinoid compounds — and provides illustrations that make it easy for a layperson to understand.

Adams said, “Dravet Syndrome is similar to diabetes and thyroid conditions. If you have severe diabetes, you take insulin; if you have seizures like Dravet, you take cannabanoids to make up for what the body doesn’t produce naturally.”

Modesto cannabis dispensary owner Jason David created a product he calls “Jayden’s Juice” that contains THC and THCA for his son, Jaydon. Like Brooke, Jaydon was diagnosed with Dravet’s Syndrome when he was an infant. Not surprisingly, the emotional support Adams receives from David counts greatly, as does the medicine itself.

Brooke also takes CBD, which Adams buys from Charlotte’s Web in Colorado. That product is named after Charlotte Figi, who suffered from seizures and Dravet Syndrome, and was greatly helped by medical marijuana.

Brooke’s “cocktail” includes CBDA and CBG both from Myriam’s Hope, a Nevada-based company that manufactures cannabis oils that help with seizures. Adams spends $450 a month on medicine for her daughter. The money is all out of pocket, though some companies offer discounts to patients with disabilities. The Adams family belongs to Kaiser, but Kaiser doesn’t approve of medicinal cannabis.

If the federal government would get with a medical cannabis program, Adams wouldn’t have to drive to Modesto. She wouldn’t need her extensive support system, and she wouldn’t have had to take on the Rincon Valley School District, which didn’t want a drop or even a seed of cannabis on campus.

The district didn’t even want Brooke to travel with her cannabis medicine on the same school bus as other students. As a result of that policy, Brooke attended a private preschool, paid for by the district for two years. Later, she was home schooled. Adams took the district to court and won her case, thanks in part to attorney, Joe Rogoway and her own persistence.

“Call it a mother’s intuition,” she said. “I wanted the best life for my kid. I still do.”

One of the most heart-breaking aspects of the story is that the school district treated Brooke as though she had a contagious disease and ostracized her because of the stigma associated with cannabis and federal laws that make it illegal.

The story isn’t over yet. Adams keeps a close eye on her daughter. She has support from her group.

“I hope our story will help other parents and children,” Adams said. “Not all mothers and fathers know they can question doctors. We had to look for answers on our own. If you have to, you can take on a school district and the medical system.”

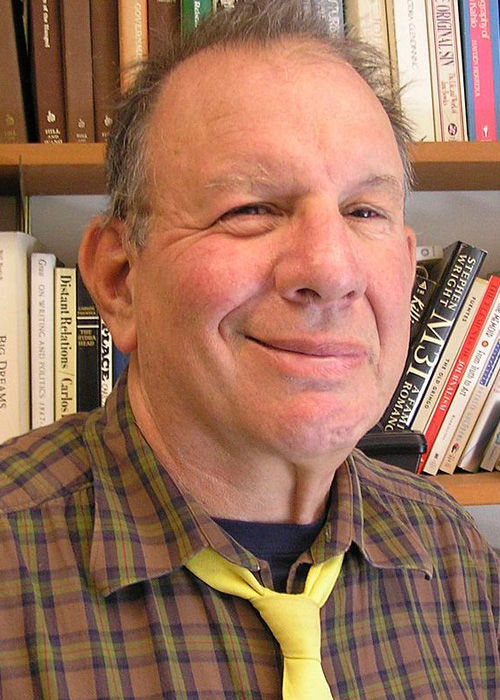

Jonah Raskin is the author of Dark Day, Dark Night: A Marijuana Murder Mystery.