When the sound and the fury, the smoke and the flames dispersed, Measure O went down to a definitive defeat, roughly at a 60-40 split. Clearly this was not what the Healdsburg City Council intended when in June they rationalized themselves into putting it on the General Election ballot.

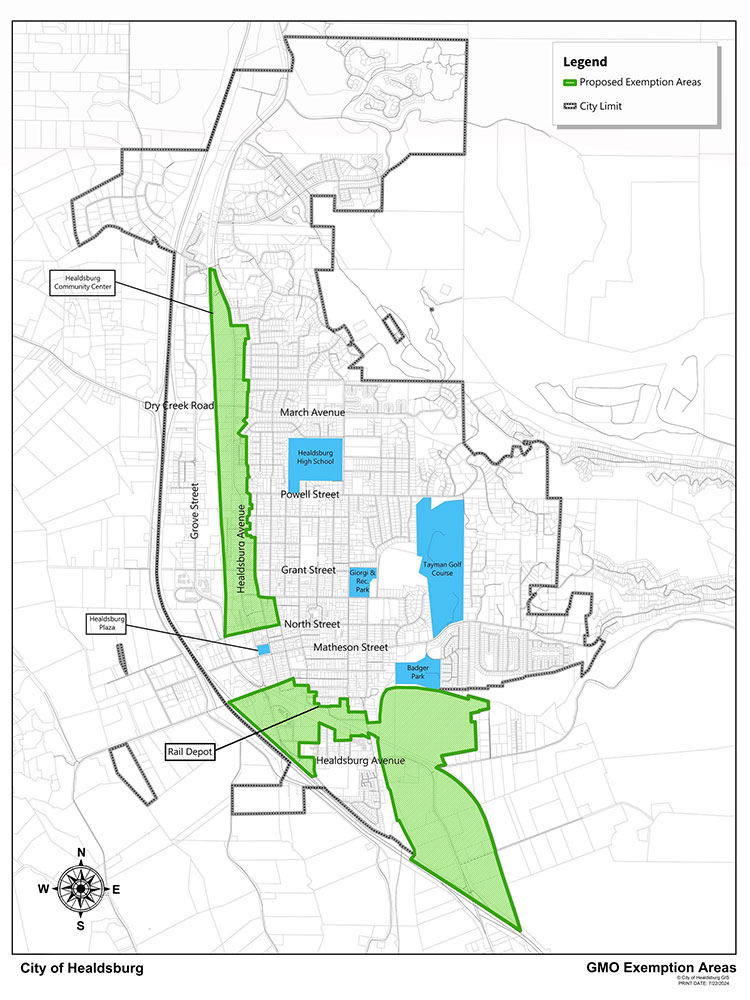

The measure question was straightforward: “To encourage creation of middle class and workforce housing on underutilized parcels, should the City of Healdsburg exempt multi-family housing along certain portions of the Healdsburg Avenue corridor from the Growth Management Ordinance?”

To arrive at the borders of the geographic exemption proposed, the city authorized some studies of resident preferences on expanding multi-unit housing, including surveys, then put the results on a map and put it to a vote.

The zone snakes down from the Healdsburg Community Center along Healdsburg Avenue to North Street. This was a bigger bite than the city’s own consultants in this measure, FM3, had recommended, and in the end that may have proven a crucial factor.

A total of 488 likely Healdsburg voters were polled, and while they favored using a “geographic exemption” to encourage creation of workforce housing, the definition in the exempted area in the survey was “within Two Blocks of Downtown – the area bounded by Grant Street to the north, Mill Street to the south, East Street to the east, and Vine Street to the west.”

By the time Measure O reached the ballot, Grant Street had become North Street, jumping over Piper to include a big chunk of what many residents consider downtown. Their downtown: a drug store, a donut shop, a health-food grocery, Healdsburg Pilates and Casa del Mole, among others.

To look at it a bit more legalistically, “According to the Citywide Design Guidelines, the downtown core’s ‘identifiable’ northern and eastern boundaries are Piper Street and East Street,” points out Jon Eisenberg, a retired attorney in Healdsburg.

He also states, with what sounds like the voice of authority, “Any definition of the ‘downtown core’ that varies from the Citywide Design Guidelines is inconsistent with the city’s General Plan, with which the city must act consistently.”

The Money Factor

The city nonetheless decided to invest in the effort to pass Measure O, despite several red flags. Following the $30,000 survey by FM3, it also allocated nearly $100,000 to promote and pass the measure.

The Yes on Measure O committee filed their campaign financials in October, showing financial support from expected and unexpected quarters. The Yes on Measure O campaign lists as its treasurer Shaun McCaffery—a former Healdsburg City Council member and mayor, who has a seat representing the 4th District on the Sonoma County Planning Commission. Assistant treasurer is Alex Wood, a member of the Healdsburg Planning Commission and son of current Assemblyman Jim Wood.

Among the individual donors were McCaffery himself, Kelley, Serena Lourie of Cartograph Wines, and general contractor and developer Brian Spiers of Geyserville, at $1,000 each. Non-individual donors included several $1,000 donations from Political Action Committees (PACs) as well as the non-profits Corazón Healdsburg* with another $1,000 donation and the Healdsburg Parks Foundation, which notably gave $2,500 in support.

“This was a real David vs. Goliath campaign,” said Dan Pizza, a.k.a. Will Sonoma, a visible spokesperson against the measure, noting the $100,000 from the city and the $15,000 from the committee. “On the other hand, Measure O opposition spent less than $600 dollars for 200 yard signs and $100 for a website,” he said. “There were also concerned residents who put up homemade signs and mailed out postcards.”

That level of spending does not rise to the level of required reporting, so none was listed. Instead the grass-roots effort spearheaded by Pizza was backed up by a small but experienced core of community members and housing advocates, including Bruce Abramson.

“The City Council failed to address the potential unintended consequences of Measure O,” said Abramson, a former member of the Community Housing Committee. “There was a credibility issue … The council did not offer any plausible evidence that workforce housing could be built. Case studies, etc., should be conducted with definitions.”

He also raised questions about potential issues in the downtown area, including vacation rentals, investment properties, second homes and infrastructure.

Working Together

“I think it failed because people don’t trust the very issue of how we can get the kind of housing that they’re saying they’re going to get,” said Brigette Manselle, another opponent to the measure who, like Abramson, signed the arguments against the measure in the county election guide. “If it really is for the middle-class workforce housing, it has to be done with a much more precise tool other than just trusting a market.”

Councilmember Chris Herrod took on the task of arguing for the measure, but his often dismissive comments toward its opponents caused complaints even to City Council meetings. Following the vote, he said, “I don’t accept at all the criticism that the City Council imposed an unpopular housing agenda on the public. We were closely attuned to the public’s demand for housing solutions, for modest growth and for affordability. But the public did not see it that way.”

Linda Cade, another council candidate and likewise a signee of the No on O arguments, said, “I feel like once the opposition’s word got out—no thanks to city staff, council or the chamber—people voted in an attempt to maintain Healdsburg’s small-town charm and avoid so-called stack-and-pack housing in our downtown.”

Mixed Messages

Mayor David Hagele, who as a City Council member was a signatory to the Yes on O arguments in the voter information guide, said, “Elections send a message, both locally and nationally. Our job now as elected officials is to dive below the headlines and reflect on the constructive feedback and concerns we heard from our neighbors over the last few months on the campaign trail.”

Jeff Kay, the city manager, was already looking ahead. “In terms of planning efforts, I think we need to take some time to evaluate the efficacy of the various options in light of the GMO remaining in its current form,” he said. “In many cases, changes to the General Plan or Land Use Code will trigger the need for costly environmental analyses. That may not be worth it if the result is a negligible impact on housing production.”

But he also raised the immediate question of density around the projected SMART station on Harmon Street, an area included in the geographic exemption that the failed Measure O proposed.

“There is a good chance that some zoning changes may be required in order to maintain our eligibility for regional transportation funding,” he said. “Current densities around the future SMART station, for example, do not meet the expected requirements for Transit Oriented Communities and could cause us to lose funding for road improvements.”

Ariel Kelley delivered a mixed message, but a key one. “Many of the voices that chimed in regarding Measure O have been absent from the dozens of community meetings and planning workshops regarding housing in our town,” she wrote. “It would be welcome to have their voices participate in proactive positive planning of the housing they are comfortable seeing in our community.”

*Note: Corazon Healdsburg was incorrectly described as a PAC in the print version of this article. It is a 501(c)(3) non-profit whose primary focus is on charitable and educational activities.

Gee whiz! The City Council didn’t listen to the people and put Measure O on the ballot. Well, at least they put it on the ballot. 25 years ago, the City Council sold the city plot on the west side of the Plaza to M. Sehr so he could build Hotel Healdsburg. We weren’t allowed to vote on a ballot measure on that. The City Council decided on its own to turn Healdsburg into a tourist town. We didn’t get a vote.

I remember that. It previously a big grassy area where families could lounge in the sun and kids played. It was a family favorite. The sun disappeared unfortunately.