As smoke from the massive Dixie Fire made its way to Sonoma County, the Healdsburg Fire Department convened a group of fire ecologists, land management experts and stewardship specialists on Aug. 4 to provide a presentation to the community on fire ecology and how certain burns can help restore the land and work to help prevent devastating wildfires.

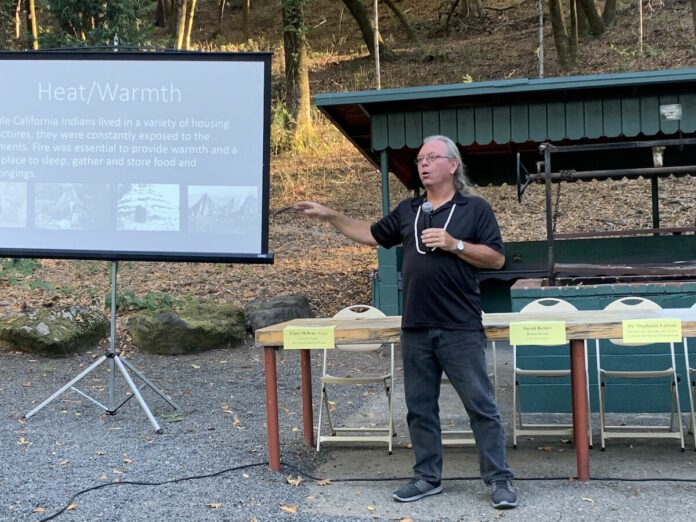

Clint McKay is a tribal citizen of the Dry Creek Band of Pomo and Wappo Indians. He’s a retired parks superintendent for the city of Santa Rosa and he spends much of his time giving fire ecology talks and working as an Indigenous education coordinator at the Pepperwood Preserve.

He also refuses to use the term “land management.”

“Management invokes that you control something, that you can control it and command it. Obviously we cannot,” McKay said. “I chuckle to myself every time I hear ‘natural resource management,’ ‘fire fuels management,’ ‘vegetation management.’ If we begin to think that we can manage fire, we’re in for a whole lot more of what we’ve been experiencing the past decade and what we are continuing to experience today.”

McKay has been advocating for cultural burns for a long time, however, the idea of using fire to prevent fire can sometimes be tenuous among fire fatigued Sonoma County residents.

He recalled a time when he was giving a similar talk near Pepperwood in Sonoma County and as he discussed the concept of using low and slow cultural burns to help prevent large fires and improve the health of forests, the tension among the crowd was so thick he could cut it with a knife.

By the end of McKay’s presentation, they had planned a burn of about 10-acres and nearby residents were asking for more.

So what is a cultural burn? Prescribed burns — such as the one conducted by the Northern Sonoma County Fire District on July 14 near Stewarts Point Skaggs Spring Road — focus on reducing fuel loads.

Cultural burns focus on, “what is in the best interest of our natural environment, all of us. Everyone, all of the organisms, all of the animals, the trees, the grass, our air, our water, our soil, erosion control, everything,” McKay said.

He said cultural burns do not put humans first.

“What happens out here affects all of us, we’re all in this together and so for indigenous people, we realize that we are simply one spoke in that wheel and we have a responsibility and our relationship with our natural environment is reciprocal,” he said. “We have to give, support and steward if we hope to get anything back. It’s not all about us.”

According to McKay, conducting regular cultural burns are extremely beneficial for the land and “helps to keep the natural world in balance.”

Fire is an important pillar in indigenous communities and is used in almost every aspect of life from cooking to hunting and for heat, ceremonial sweats and many other aspects of life.

Cultural burning of grasslands, brush, forests and woodlands helps maintain healthy habitats.

“Otherwise, things get overgrown. It also makes the game more visible … and it also provides valuable food source for not only deer, but for every animal that you can think of. When we allow things to get overgrown and they (plants and seeds) don’t reproduce and they don’t propagate, we all lose,” McKay said.

Many different flora of the region, such as various closed-cone pine species and chaparral, cannot propagate without fire. Fire can also help with sudden oak death and oak gall and can be a natural pest deterrent for critters like acorn weevils.

Additionally, “When brush and debris is allowed to accumulate, it draws things in, it draws mice, rats and rodents which call in rattlesnakes.”

Perhaps the biggest benefit of cultural burns is fire protection. Burns help remove invasive species such as French Broom and thick brush that may have accumulated over the years.

McKay pointed to a photo on the presentation screen of a small cultural burn and next to it, a photo of crown fire where a huge swath of forest was completely engulfed in flames. He said if we can’t do cultural burns like this, we can get large, destructive wildfires like the one shown in the photo.

“We’ve been advocating for fire for all of these generations because we don’t want that,” he said, referring to severe wildfires. “That is scary. That does take people and animal’s lives.”

The halt of regular cultural burns in the last century has led to an unhealthy buildup of fuels that threatens both the health of the forests and residents as more folks and developments move closer to the wildland urban interface (WUI).

Peter Nelson, a Coast Miwok and tribal citizen of the Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria who’s a professor at UC Berkeley with a background in environmental science and anthropology, said the halt of cultural burns is mostly in part due to colonialism and the reduction of the stewardship of land by local tribes.

When asked by one of the meeting attendees if the local forests are healthy, Jacob Harrower, a registered professional forester with Frontier Resource Management, said “no.”

“Most forests that I see are not (healthy) and I see a lot of forests on the daily, on the monthly. It’s really the lack of the disturbance that is needed,” Harrower said.

Nelson said the lack of cultural burns over the decades has led to a large amount of invasive species.

“A lot of people are not aware that 90% of the grasses in California are invasive species of grasses. There was almost a full type conversion from native grasses to European grasses.” he said.

Bringing animal grazing into the picture

McKay noted that a lot of the land in the area is not ready for a cultural burn, and that we need prescribed burns in order to be able to get to the point where cultural burns can be conducted.

Grazing with goats and sheep is just another tool in the fire fuels work toolbox and can get to places like steep terrain where it may be difficult to conduct a prescribed burn.

“We had poison oak, we had English ivy and you can see what a great job they’ve done to make this neighborhood a lot safer. Right now as we speak we have wildfires going throughout California … We’re looking at ways… and going to see what we can do for fire fuels management,” said Healdsburg Division Chief and Fire Marshall Linda Collister.

Roughly 220 goats are on Fitch Mountain doing fuel reduction work.The goat grazing is just the start in getting the Fitch Mountain area back to a safe and healthy state.

Collister said they want to work on erosion control around the mountain and to have a registered forester update the community’s vegetation management plan.

“Eventually, we want to do a prescribed burn at the top of Fitch Mountain and then eventually we’re going to be able to do our cultural burns,” Collister said.