Sonoma County schools tackle the challenge of online education

In what may be one of the biggest educational experiments ever, Sonoma County students will spend the next several weeks — and if Gov. Gavin Newsom is correct, the next several months — going to school online.

The county’s decision to close schools as a way of flattening the curve of the coronavirus pandemic took many parents by surprise, but the Sonoma County Office of Education (SCOE) had been planning for this eventuality since the middle of February.

“We realized this was going to be an issue long before schools closed,” said Matt O’Donnell, SCOE’s tech education specialist. “Schools in Japan were closed, schools in Italy were closed and we thought that this was a possibility for us as well.”

O’Donnell and Sonoma County Superintendent of Schools Steve Herrington got together to lay out a plan of action.

Getting students ready to learn online

“Before you can just switch to online education, you have to make sure that you have the infrastructure in place,” O’Donnell said.

The first thing SCOE did was to ask schools to do a tech audit to determine which students had computers with internet access at home and which students would need to borrow those from the school.

Because it suspected that a school closure was imminent, SCOE warned schools to send kids home at spring break with school computers and to loan them hotspots if needed so that they could access the internet.

Some schools, like those in Cloverdale and Healdsburg, have a one-to-one ratio of children to computers, at least in the upper grades.

“All our students from grade six to grade 12 are issued a Chromebook by the district,” said Healdsburg High School principal Bill Halliday. “We also check out wireless hotspots for students, and we’ve purchased more of them in light of our virtual school plan.”

West county isn’t so lucky. There are 72 students in the West Sonoma County Union High School District (WSCUHSD) who don’t have access to a computer with internet at home, but the district is managing nonetheless.

“Prior to spring break, we surveyed students to assess both availability of devices and internet access,” said Toni Beal, superintendent of WSCUHSD. “We checked out devices to all students who did not have one. For any students that did not receive a device prior to spring break, devices are being checked out to them this week. We are in the process of working with service providers to secure internet access for students without access. In the case that we cannot provide that access, we will make arrangements to get curriculum to students in another way.”

Getting teachers ready to teach online

While the schools worked on sussing out their students’ technical readiness for online education, Herrington and O’Donnell set up a webinar to meet with district leadership about what the schools themselves needed to do to get ready for online learning.

“It’s one thing when your teachers are trained (to teach online), and everybody has internet access,” O’Donnell said. “Then you could just flip the switch, the way companies like Twitter and Google do when they say ‘Hey, we’re working from home.’ It’s not as easy for school districts, especially in Sonoma County with 40 different school districts with different levels of readiness.”

Teachers run the gamut of tech readiness, from technically adept to technophobic. For many teachers, even those comfortable with technology, the suddenness of the shift has been deeply unsettling.

“I am feeling overwhelmed at the prospect of providing excellent education via the distance learning mode with such little time to prepare,” said El Molino math teacher Rachel Lasek. “Most of us are not used to teaching digitally, nor are our students used to learning digitally.”

But teachers are resourceful, and even some who were originally skeptical about the shift are getting more comfortable with the idea.

“If you asked me a few days ago, I would have said that I feel horrible about the whole thing,” said Emily Akinshin, a fourth grade teacher at Oak Grove Elementary in Graton. “People learn best in community, with support from one another and building on each other’s ideas. The thought of handing out meaningless packets and having students watch videos in isolation is not quality learning.”

“However, after reaching out to my awesome fourth grade team — Carinne Paddock and Diana Denisoff — I have learned of an online platform that can connect teachers to students and students to each other. While I still have concerns, especially for students who might not be able to connect remotely, I feel better knowing that I can provide a learning experience closer to what our class experience is like.”

What online education looks like

O’Donnell thinks some parents may be surprised by what online education looks like.

“People think it’s gonna be like a Zoom call, where the teachers are there and all the students are present,” he said. “I just don’t think that’s going to be feasible given the different quality of internet connections for students.”

Instead, he said, most teachers will be using “asynchronous” online learning, meaning the teacher and the student won’t be in a virtual room together the way they are in classroom. Instead, teachers will give students assignments online — readings, lectures or projects to work on — and students will work independently, checking in with teachers when they have a question, usually through email or during virtual office hours.

“Right now, students just need to know it’s going to be okay,” O’Donnell said. “They need some simple structure in their lives and some simple consistency and then teachers can do what has worked best in their classroom and try to make it look like that as much as possible, understanding that it’s not going to be perfect.”

One of the decisions SCOE made early on was not to enforce a one-size-fits-all approach to online learning.

“It’s not going to be the same for every school,” O’Donnell said.

For one thing, online learning looks different for older versus younger students.

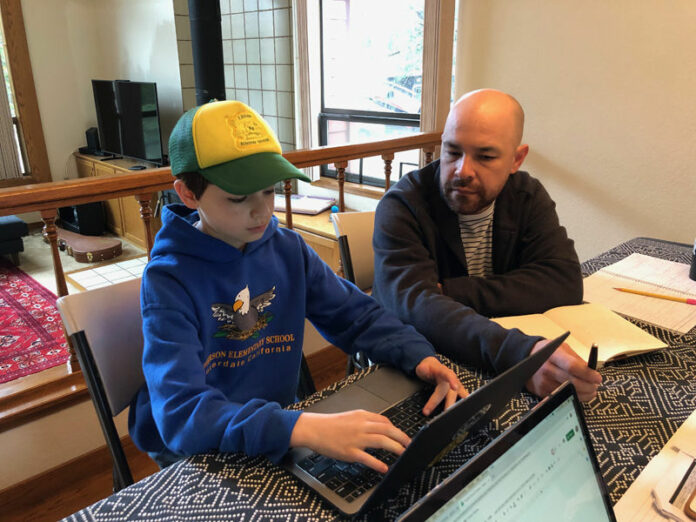

“Students in high school have much more agency over their learning,” O’Donnell said. “You could put a couple of assignments on Google Classroom, they could turn them in, you can give them feedback and that’d be fine. Younger students need more help, and they’re going to need a lot more parent involvement.”

Though O’Donnell encourages teachers to use the platforms they’re most familiar with, he does have some favorites.

Google Classroom

“Google Classroom looks like a Facebook page almost, where a teacher could post a video, assignments or a link to a website or documents. Students could submit their work the same way or ask questions,” he said.

“The nice thing about Google Classroom is it’s one platform — so if you’re in high school, all your classes will be on that same platform,” O’Donnell said. “You don’t have to go to a different platform for your English class or your history class or your math class. They’re are all in one place.”

(See a tour of Google Classroom 2020 here: youtube.com/watch?v=2Iowi-gmbys)

Seesaw

For the lower grades, O’Donnell likes Seesaw, a simple portfolio program for children who are too young to type.

“For lower grades, Seesaw is a decent one that does digital portfolios so kids can showcase their learning,” he said. “It’s really simple to use.”

On Seesaw, teachers write the assignments for the day on the assignment page.

“The assignment might be something like, ‘Draw a picture of a plant,’” O’Donnell said.

The child would draw a plant with crayons or pencil on real paper. Then they or their parent would snap a photo of their work with their cellphone and upload it to the Seesaw site.

“Or maybe it would be ‘Write a sentence about a picture book you read.’ Then they’d write the sentence and they take a picture of that too, and pretty soon you’d have this portfolio of the different things they’ve accomplished,” O’Donnell said.

What are teachers doing over the next few weeks?

In her fourth grade classroom, Akinshin said she will be using Google Classroom and a few other online programs.

“Our entire district has two programs this year called Lexia and Dreambox. They are supplemental programs established to help differentiate the curriculum in math and language arts,” she said. “Students have access to those programs at home.”

In addition, she said, “All of our students have district Gmail accounts. My students also have a Google Classroom account and are familiar with Google Docs and Google Slides. I am working with my team to figure out how to best use those tools.”

Lasek will be using Google Classroom for her classes as well.

“I use Google Classroom regularly with my students. I have often posted extra resources and videos to support student learning, but have never used the site as the sole location for instruction,” she said. “I have used Desmos.com for student learning opportunities, as well as other online games for differentiated practice. I have also made videos for my students to support in classroom instruction. We will continue to use Google Classroom as our school’s main learning platform. Many teachers will use Zoom to provide live conferences.”

In Cloverdale, Cloverdale High School English teacher Jacob Ramirez is also using Google Classroom.

“It’s just sort of a staple now,” he said. “We’ve also been doing something called Grammar 101 for supplementary instruction in grammar.

“A lot of the things that we’re really relying on now, the kids are already familiar with so they’ll be really good assets for us moving into online learning.”

The silver lining

Back at SCOE, O’Donnell knows that shifting to online learning, even temporarily, will be challenging, but he thinks the current crisis could be a watershed moment for online education in Sonoma County.

“I think people are finally going to realize the equity issues of people not having internet access across Sonoma County and are going to work to find ways to make that feasible,” he said.

“The other thing people are going to realize is how important it is for students to have tech skills. They’re also going to discover what a huge array of resources there are online in all subject areas, as well as the tremendous number of learning opportunities that are available to students online.”

“SCOE has been preparing for something like this for the last few years,” he said. “We’ve been working with districts to help them become more 21st century savvy in their education. We’ve been putting effort and resources into this, and it’s really going to pay off.”