Not that long ago, cannabis was a part of agriculture, and before that it was part of the counterculture.

Now it’s an “industry,” and, like all industries, it needs both capital and labor.

Unions have been slow to move into the cannabis world because it’s been illegal and on the black market. Outlaws and criminals looked to “gangs” for protection, not to unions, which lobby for higher wages and improved working conditions.

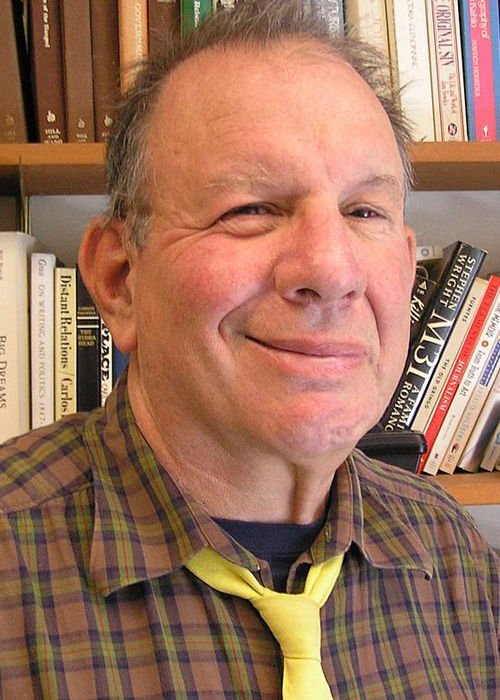

Now that cannabis is regulated by the state of California, with taxes and inspectors, union organizers have swooped down and moved in, albeit gently. James Araby is one of them.

A 10-year veteran with the United Food & Commercial Workers Union (UFCW) local 5, Araby is proud of his union and the unequivocal support it gave to Proposition 64, which legalized marijuana in 2016.

“On the state level, cannabis is accepted as a legal industry, but on the local level it’s a different story,” Araby said. “Eighty percent of the cities in California still don’t have provision for the legal sale of marijuana. Even in the Bay Area there’s a lot of fear-mongering.”

Indeed, foes of cannabis still spread misinformation, though few people claim that marijuana users commit acts of murder and mayhem. We’re no longer in the “dark ages,” though in some parts of California the dark ages survived longer than in other places.

Contra Costa County, an hour and some minutes from San Francisco, is one of them.

A leaflet recently distributed in Contra Costa by The Pacific Justice Institute — an organization devoted to “religious freedom, parental rights and civil liberties” — claimed that “marijuana is a dangerous, psychoactive drug,” that smoking it is worse than smoking tobacco, and that marijuana users commit “violent” acts and go on to other drugs.

Araby has a tough row to hoe in Contra Costa, where he has an office in Martinez, the county seat.

“In Contra Costa, there’s been a ban on the whole cannabis industry,” Araby said. “People want to put the genie back in the bottle.”

But even Contra Costa has become more cannabis-friendly.

There are now two cannabis dispensaries in the county. Moreover, the city of Concord has authorized 10 cannabis licenses for testing, manufacturing and distribution of cannabis. It’s considering a license for a dispensary. Contra Costa isn’t yet like Sonoma, but it’s catching up.

Araby understands why counties have been slow to issue licenses.

“There’s uncertainty about the long-term health impacts of cannabis,” he said. “And certain ethnic groups don’t support legalization.”

Indeed, older Chinese men and women remember opium and heroin addictions and put marijuana in the same category. But the Chinese are not the only group opposed to the legalization of cannabis. Many cops have not shed the old prohibition model and not without some justification.

“The police don’t have clarity about how to enforce the law,” Araby said. “Administrators have a lack of will because they’re afraid of law suits. There’s also institutional resistance.”

Nevertheless, Araby carries on the fight, both for the cannabis industry as a whole and for workers in that industry. If there’s no industry, there won’t be any workers to organize.

“Belonging to a union gives employees a seat at the table,” Araby said. “The union provides a voice at the workplace and a political voice, too, at the local and state level.”

Araby thinks it will be three to five years before the cannabis industry stabilizes. He also thinks that more California cities will follow the example of Contra Costa, relax opposition to cannabis and open the doors to the industry.

Araby has little if any doubt that cannabis will continue to be a growth industry and that it will find a place in the economy. What’s admirable about Araby is his honesty.

Emergency rooms, he explained, are seeing more and more people who have “cannabis hyperemesis syndrome,” otherwise known as CHS, which results from long-term use and abuse of cannabis. It can lead to nausea, vomiting, gastrointestinal discomfort and abdominal pain. Though it’s a rare condition, it’s troublesome.

The cure: don’t use cannabis and take hot showers. Paradoxically, cannabis is also an anti-emetic: a drug that’s effective against vomiting and nausea.

Araby explains that some states in the U.S. allow for workers to use cannabis for medical reasons, but that workers who test positive for THC can be fired.

That’s another valid reason for a union. After my interview with Araby, I wondered if any workers ought to be allowed to use cannabis on the job. Maybe some, but definitely not those who operate forklifts, drive eighteen-wheelers or perform surgery in an operating room.

Rules can feel onerous; people don’t like to be told what to do. But when you come out of the woods and join a community of fellow humans, you have to accept rules and give up some freedoms.

That’s what my father, who was a lawyer, told me when I was a boy. It was good advice then and it’s good advice now.

Jonah Raskin, a professor emeritus at Sonoma State University, is the author most recently of “Dark Day, Dark Night: A Marijuana Murder Mystery.”