Sonoma County Regional Parks is finding new ways to engage with folks during the COVID-19 pandemic, and on May 29 they offered a free webinar on fire ecology, the study of how environments change and adapt after a large wildfire event.

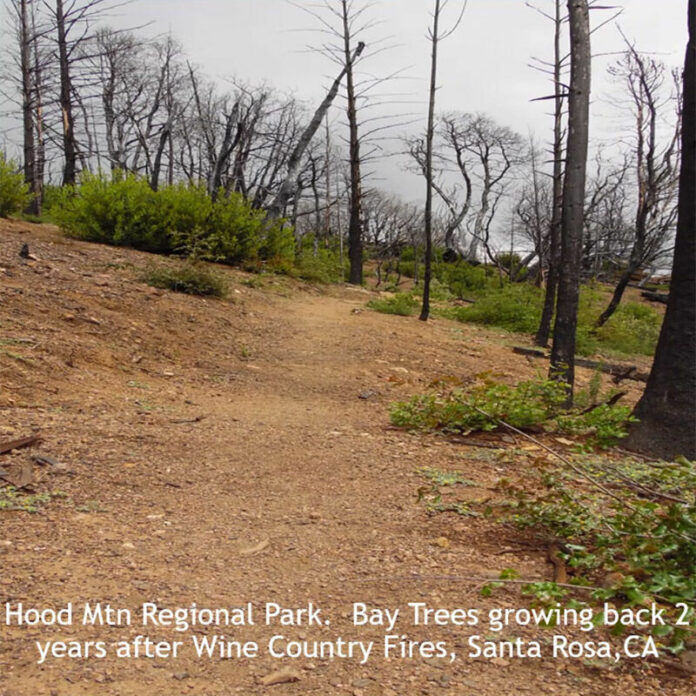

While wildfires leaves burn scars that may seem detrimental to the environment, wildfires and periodic burns are actually part of a healthy life cycle for forests, giving birth to plants that can only thrive after a fire, creating ample food and shelter for animals returning to the area, a process that’s now occurring at recovering parks such as Hood Mountain and Foothill Regional Park.

During her Friday presentation, Katja Svendsen, an environmental educator with Sonoma County Regional Parks, discussed the various types of native plants that thrive in heat and fire.

“This picture was taken up at Hood Mountain Regional Park and this is a plant called ‘Indian warrior,’” a small plant with bright pink flowers that is typically found in oak woodlands and low elevation areas throughout California and Oregon. “This was taken two years after the 2017 wine country fires.” The photo shows the little plant thriving.

A plant called “Whispering bells,” is another hearty plant that flourishes with fire.

“This next one is a rare plant, a plant we don’t see very often. It is also at Hood Mountain Regional Park, and it is called ‘Whispering bells,’ (a bell-shaped yellow flower as the name suggests). The seeds lay dormant in the seed bank for up to 50 to 100 years. When a fire sweeps through and burns the whole forest down we see these plants reemerge,” Svendsen said.

When the forest grows back up after a fire and creates more shade, the plant will go back into the dormant seedling stage until another fire coaxes it out.

Sorroutenous cones are another kind of flora that need fire and heat to pop open and seed.

“They can only open with fire or intense heat,” she said.

Some of these special cones can give birth to the “Nob cone pine.”

“With intense heat they will open up the cones and the seeds will disperse. If we don’t have fire, these trees will not germinate,” Svendsen said.

The sergeant cypress is another type of tree that won’t germinate unless its cones open from the heat of flames, and according to Svendsen, after the 2017 fires sergeant cypress trees were seen growing at Hood Mountain.

“I have been up to Hood Mountain recently, and there have been little sergeant cypresses growing up, which tells us it (the fire) is doing its job,” she said.

Animals return to Foothill

One month after the Kincade Fire burned through sections of Foothill Regional Park in Windsor, a young buck returned to the area, a familiar and welcome sight.

Svendsen showed a photo of the buck walking through the grass, looking for something to munch on.

“It shows that even one month after a fire, there is ample food and shelter and habitat for these animals,” Svendsen said.

Regional park wildlife cameras set up at various locations have also been capturing animals and their return to their local habitat. Cameras at Sonoma Valley and Taylor Mountain Regional Parks have caught a slew of wildlife activity, from possums, to coyotes, skunks, families of deer and mountain lions.

You can check out their wildlife camera videos on the Sonoma County Regional Parks Facebook page.

The role of fire

The fire cycle, Svendsen said, is sort of like nature’s cleaning service; it cleans out the forest.

“I don’t know if you’ve gone walking in any of our regional parks that were burned, but it’s a cleansing renewal. It burns everything down, and it looks bleak, but then two to three weeks afterwards there is grass and plants growing, animals come back as we’ve seen and the trees grow up and they start to become mature,” she said.

She said historically forests in the area were not as dense and trees were thinner and spaced further apart due to more periodic burns and fuel burns done by the natives that lived in the area.

“These forests had time to adapt to the periodic burn and then a big fire happened in Idaho and Montana in the early 1900s called ‘The Big Burn,’ and it produced the new forest services and the government to say ‘Let’s suppress every single fire we see’ and that started 150 years of forests adapting to no fire,” Svendsen said.

Now, forests are more dense with thick understories, which means when fire rushes through there is more fuel to burn, creating larger and nastier fires.

“The forest we see today is understory. The plants you see under the canopy of the forest, we also call these fuels,” she explained.

When fuels are used up in a fire, more can grow, and by the time a new wildland fire occurs the forest canopy is brimming with fuels.

Helping forests stay healthy

However, there are ways to help forests stay healthy and reduce fire fuels so in the event of a fire, there’s less fuel to burn and more fire breaks. This is where the phrase, “Log it, graze it, or watch it burn” comes into play.

She said at the regional parks, they’ve implemented several grazing programs. There was one at Spring Lake Regional Park and one at Helen Putnam Regional Park that utilized goats and sheep.

Svendsen said, “The other day, I was driving up Fountaingrove, and there were goats grazing up there. They mowed down all of the tall fuels.”

Fuel breaks like wetlands are also important. A wetland area sandwiched between homes and Foothill Regional Park provided an additional fire break from the Kincade Fire breaking into the town of Windsor and residential area.

Periodic prescribed burning done right by entities like CalFire also helps reduce fire fuels so when fires come through they are not as catastrophic, and they’re more of a “good/healthy” fire.

“The good fire is getting rid of the invasive species we see, bringing back the native species. It is burning that understory,” she said.

According to Svendsen, prescribed burn associations are gaining momentum in California and consist of landowners and neighbors who want to put the “good fire” on the land as a way to mitigate major wildfire risk.

“When a fire goes into a burn scar (or an area where there’s been a prescribed burn or fire fuel reduction work), there is not much vegetation there, and the flames laid down a little bit in Kincade and it allowed firefighters to be able to get access around the control lines,” she said.