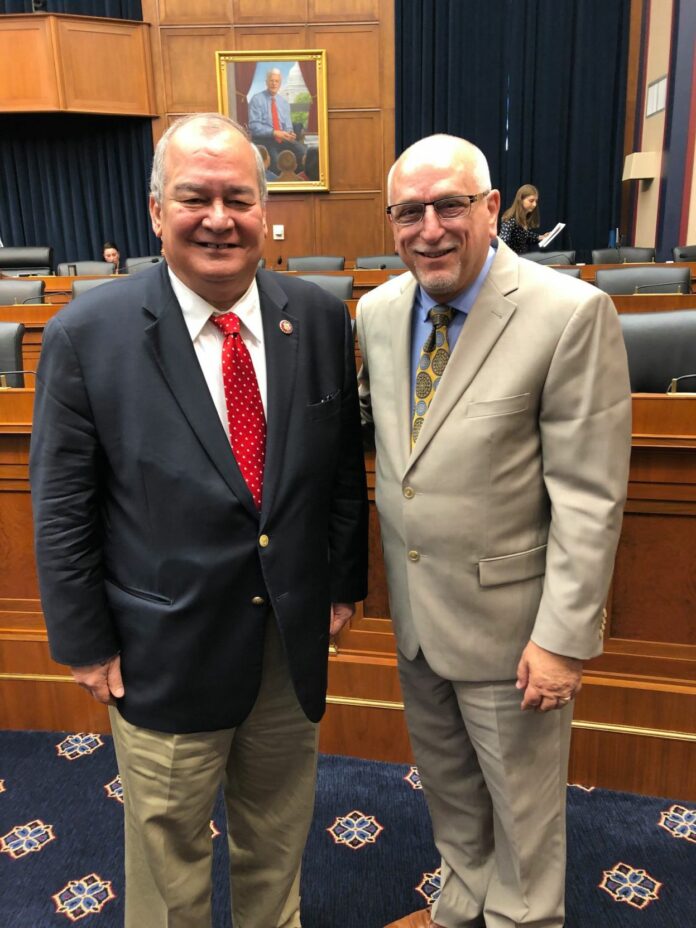

On June 5, Steven D. Herrington, Sonoma County Superintendent of Schools, testified before the U.S. House Subcommittee on Early Childhood, Elementary and Secondary Education. The hearing, titled, “This is Not a Drill: Education-Related Response and Recovery in the Wake of Natural Disasters” was held at the Rayburn House Office Building on Capitol Hill in Washington, D.C.

According to a statement, Herrington was invited to testify to share insight and lessons learned from responding to the 2017 Tubbs Fire in Sonoma County, at the time the most destructive wildfire in state history. In addition, he discussed how he assisted other California superintendents through similar fire disasters in the following year.

“I’d like to share with you the lessons I and my colleagues have learned from these disasters and how, I believe, the federal government can best help schools reopen their doors after a large-scale crisis,” he said during opening comments.

Herrington had seven talking points in his testimony, aimed at where assistance and guidance on the federal level could help local school districts: reopening schools, school facilities, grants, reimbursement, preparation, supporting testing waivers for impacted communities and mental health support.

“There are protocols for ensuring safety and reopening school sites after earthquakes, but prior to the October 2017 Tubbs fire, none were in place for opening school sites impacted by toxic ash, debris and smoke,” Herrington said as he described the challenge of figuring out when to put students back in the classroom. “A special state task force convened by the California Department of Education and Office of Emergency Services was very helpful in assisting districts to find solutions. However, I believe that a state or federal standard is needed that can guide a school district superintendent through the process of determining whether it is safe to reopen school after a wildfire. Also, guidance is needed for districts and counties from the Environmental Protection Agency regarding how toxic ash should be dealt with.”

Similarly he described the challenge of finding alternate sites when schools are too damaged to re-open.

“If the federal government could provide portable structures that meet required standards to serve as temporary school facilities, it would greatly increase the speed with which school could return to session,” he said.

While he praised the many grant programs available to get schools back on their feet, Herrington stated that timetables and the variety of organizations that must be dealt with, including but not limited to insurance providers, FEMA and state and federal government partners when determining how and when expenses will be reimbursed, without clearly defined limits and few assurances, can result in a lack of certainty and underused funds.

“Programs should give school leaders the time they need to assess the full breadth of impacts with confidence that funding will be available to meet students’ needs,” he said. “The California County Superintendents Educational Services Association (CCSESA) has requested that Congress allow for extended time to use federal grant funds allocated for the 2017 fires as well as grant the ability to use these funds for 2018 fires.”

In addition, according to Herrington, schools had trouble managing the processes of reimbursements for expenses.

“Some of our schools found that they were not able to be reimbursed for expenses that quickly accumulated after opening to the community as emergency shelters because the proper chain of command could not be identified after the fact, even though the request had come from the Office of Emergency Services.

“Most school leaders are not emergency professionals. In the middle of a chaotic situation, those responding, filling out forms and completing processes will not always be able to follow every protocol 100% correctly … we ask that there be additional understanding and flexibility built into the FEMA reimbursement process that accounts for these factors and allow for small variances from standards,” Herrington said.

He also asked them to consider having FEMA cover expenses for specialist and consultant post-disaster.

“Emergency disaster experts and consultants can be a much-needed resource for administrators while they tend to their regular responsibilities in addition to addressing heightened student needs, often for months or years,” he said.

He also encouraged greater interaction between FEMA and schools before disaster strikes, so schools can be prepared for any emergencies.

“FEMA could increase its outreach to schools to inform them of the ways that they can prepare for a disaster. My office has applied for a grant to create a hazard mitigation plan for all the schools in Sonoma County. Generally, schools are omitted from county and city hazard mitigation plans. We recently learned that schools are eligible for dedicated FEMA recovery funds if they have a hazard mitigation plan in place when disaster strikes,” he said.

Herrington pulled no punches when it came to the need to have some flexibility for impacted districts. The Santa Rosa School District had requested a waiver for its standardized tests since schools had been closed for weeks due to the 2017 wildfires.

“The federal department of education did not grant the district’s request for a testing waiver. As a result, the district was given all orange scores on the state’s accountability metric (the second to lowest performance category). This provided false and unhelpful data that will skew the district’s accountability ratings for two full years based on the way school success is measured in California,” he said. “We propose that the federal government give states local control in deciding when testing waivers are appropriate following a disaster.”

Finally, Herrington spoke to the severe mental trauma left behind by the fires.

“In a recent survey we conducted, Sonoma County school districts reported that more than 2,900 of the county’s 70,000 students were still exhibiting increased anxiety, stress, depression, behavioral problems, or decreased academic performance as a result of the 2017 wildfire. The same was true for more than 400 school employees,” he said. “A superintendent with one large school district wrote, ‘There is a significant increase in fear, anxiety and the near inability to navigate through changes and ‘unknown’ situations. Kids are exhibiting far more ‘giving up’ than ever seen prior to 2017.’ Most concerningly, he added that there had been a significant increase in suicidal threats or attempts.”

He also expressed concern “that long-term emotional stress will continue to show up and be exacerbated by other significant fires within or outside the county. This was clearly seen last year when heavy, toxic smoke from the Camp Fire descended on our community. Teachers reported kindergarten children crying and running inside after seeing the smoke while on the playground. Staff and parents were equally stressed,” he said.

“I encourage you to consider creating a dedicated source of funding for this. Schools would welcome any financial assistance that the federal government could provide in order to fund sustained counseling and mental health support for a minimum of three years. Addressing student and teacher trauma will enable our communities to heal and our students to thrive and develop resilience in the face of adversity,” he concluded.

Other individuals testifying included Frank T. Brogan, assistant secretary for elementary and second education, U.S. Dept. of Education; Glenn Muna, commissioner, CNMI Public School System, Saipan; Rosa Soto-Thomas, St. Croix Federal of Teachers, Kingshill, St. Croix, Virgin Islands; and, John L. Winn, former Florida Commissioner of Education, Tallahassee, Florida.