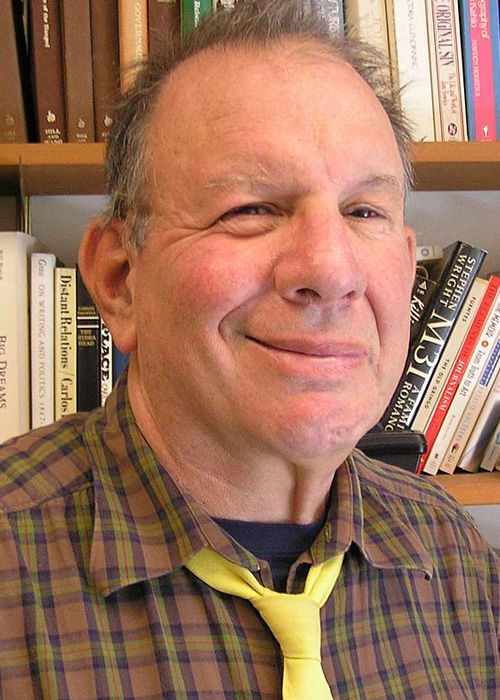

Dennis Hunter: Outlaw Turned Cannabis CEO

When I think of Dennis Hunter, 45, clichés come to mind like a flock of birds landing on an overhead telephone wire. Clichés also come to Hunter’s mind. I don’t mean that as a criticism. After all, behind almost every cliché there’s a truth. Indeed, it takes a thief to catch a thief and to know what’s legal and what’s not it helps to be an outlaw.

Listen to Hunter talk and you’ll probably hear him say that his life has been a series of rollercoaster rides, that he was the black sheep in his family and an embarrassment to one and all.

Hunter would also probably say, as he said to me during an interview at his company, Cannacraft, that he was for many years ahead of the cannabis curve and that the curve finally caught up with him. A longtime ex-outlaw, he has made a successful transition to the world of law and order. You might now call him a model citizen, albeit with a checkered past.

“I had to do it the wrong way before I found the right way,”

Hunter told me. He added, “Still, I wouldn’t take back anything that I’ve done.” Indeed, outlaws rarely seem to be sorry for the wrongs they’ve done. These just move on.

These days, Hunter is probably as necessary as the lawmakers themselves to engineer a successful shift from illegal to legal cannabis. He’s doing all he can do to make that happen.

The CEO at Cannacraft—a multi-million dollar business that manufactures smoke-free cannabis products—Hunter lives in Rohnert Park, a short drive from his company’s 36,000-square-foot corporate headquarters in Santa Rosa.

Yes, cannabis has gone corporate in Sonoma County where folks often sing the praises of small, local and organic. Hunter sings them, too, though he’s gone big with products that are available all across California.

These days, he educates Sacramento lawmakers about the cannabis manufacturing industry that he has helped to build from the ground up. Neither a grower nor a dealer, Hunter is the face of the cannabis future that’s coming soon to a dispensary in your town, or close to it. The old-fashioned joint is still popular, but vaporizers and edibles are inching up and Hunter is pushing them as fast as he can.

Last year, he offered his expertise to State Assemblyman Ken Cooley (D-Rancho Cordova). Cooley drafted AB 2679 that created the guidelines for the safe manufacture of cannabis oils, tinctures, creams and more. He and his fellow assemblymen in Sacramento knew heaps about growing and selling cannabis. They didn’t know about manufacturing the products that are derived from the plant.

Hunter provided them with essential information about the industry. AB 2679 also created safeguards for manufacturers like Hunter who finds it ironical that he has testified about cannabis before some of the same law officers who once arrested him.

“Now, I’m the expert,” he says a tad boastfully. “They listen to me.”

Born in Arcata in 1972, when hippies from the Bay Area and beyond were beginning to grow pot commercially in northern California, Hunter moved down to Willits in 1985 at 13. There he discovered that “sinsemilla”—the Spanish word for without seeds, as growers then called cannabis — had become Mendocino’s number one cash crop. The lumber industry had declined, unemployment had risen, and hard-working men went looking for something lucrative to do with their hands. Hunter was among them, though just a boy.

“I went into the hills and discovered folks who were very cannabis friendly,” Hunter told me. “They were creative, led interesting lives and enjoyed almost everything they did.”

Indeed, men who had worked as loggers and in mills joined hippies, swapped seeds and know-how. For a time, it seemed that everyone in the hills of Mendocino, from Yorkville to Covelo and Hearst, grew weed. One generation of farmers followed another.

In the 1990s, the “hipnecks”—the hybridized sons and daughters of the hippies and rednecks — discovered they had a lucrative crop in common that far outweighed their cultural differences. They were also far less idealist than the originally hippies.

Hunter grew way more marijuana than Mendocino County rules allowed. Arrested and found guilty of illegal cultivation, he spent 200 days in the county jail in Ukiah. When he was released he moved north, settled in Humboldt and went back to the only trade he really knew. He was arrested again, this time by the Feds, in 2002.

“They flew-over my property,” Hunter told me. “All that green vegetation on the ground looked suspicious, which led them to an investigation and papers that had my name on them.”

This time Hunter served 6 ½ years in two federal prisons, one in Oregon, the other in Nevada.

“They’re nicer than county jails,” he said. “They have libraries, classes you can take and yards where you can get exercise.” No bitterness there.

After he was released, Hunter decided to adhere to the law as best he could, though he also wanted to stay in the business of cannabis, or “cannabiz” as it’s called.

In 2014, he founded Cannacraft and thought he was home free. Then, in the summer of 2016, Sonoma County law-enforcement officers raided his place and took him to jail. Charged with the illegal use of dangerous chemicals and the unlawful manufacture of cannabis products, he was back on his roller coaster ride again, and very near the bottom, or so it felt.

In fact, this time the police had it wrong. Hunter and Cannacraft were playing by the rules. No dangerous chemical were used and nothing illegal took place at the manufacturing center. Hunter was released. Charges were dropped, his property and his money—which had been seized—were returned.

Now, nearly a year later and hard at work, he ploughs almost all profits back into the business.

“Now is the time to grow Cannacraft,” he told me. “Time to get busy.” Indeed, before the competition becomes even stiffer.

In the evening, Hunter relaxes with a joint, a bong or with one of the smokeless products that Cannacraft manufactures.

“Cannabis opens me up,” he told me. “When I hike it takes me into the heart of nature. During sex, it allows me to be in touch with my partner.”

In an age when few cannabis spokesmen or women talk openly about sex and pot, Hunter does just that in a non-preachy way.

About the future of the industry he’s optimistic.

“I don’t think the Trump people are going to go after medical cannabis,” Hunter told me. “They have too many other battles to fight. If anything this administration will have more bark than bite.”

How’s that for a cliché, Mr. Trump?

Jonah Raskin, a professor emeritus at Sonoma State University, is the author of Marijuanaland, Dispatches from an American War, published in French as well as English, and shares story credit for the feature length pot film Homegrown.

51.4

F

Healdsburg

December 24, 2024