Last summer, I befriended a woman from Laos who worked on a Sonoma County marijuana plantation. Three other Laotians worked with her. All of them belonged to the Hmong, an ethnic group that has lived for thousands of years in the highlands of Southeast Asia.

Many still live there, though 300,000 or so are in the U.S and about 100,000 in California. Some grow marijuana crops on the North Coast. Some go to jail for cultivation.

In the 1960s and 1970s, the Hmong cultivated opium poppies and worked with the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) to battle the communists who defeated U.S. forces and seized control of Vietnam.

While CIA operatives didn’t actually smuggle heroin, they provided drug lords with airplanes, arms and political protection. When Alfred McCoy broke the story in his book, “The Politics of Heroin in Southeast Asia,” it was a big scandal.

The Hmong woman I knew better than any of the others was named Tia. She was 52 years old and she came to the U.S. in 1976 with her older sister. Their parents arrived four years later.

“The Hmong helped the CIA,” Tia told me. “In exchange, they brought us to the U.S. I like it here because we have freedom.”

Tia remembered her mountain village. “Families had plots of land, grew rice and vegetables,” Tia explained. “If no rain, no water and so no crops, not like here where have wells and irrigation.”

Last summer, Tia worked 12-hour days and was paid $15 an hour, $5 less than the white guys. It was 90 degrees in the sun, but she didn’t complain. “Have no choice,” she said.

Tia and the other Hmong slept in tents near the marijuana field. They cooked their own meals — rice and vegetables — over a gas stove they brought with them. They also brought their own long-handled hoes.

Tia showed me how to use a hoe properly to make saucers that would hold water around the marijuana plants. “Important to take time, not hurry,” she said. “Make look nice and last long time.”

Even in the hot sun her whole body, except for her face, was completely covered from head to toe, while the white guys took off T-shirts and shunned hats.

Tia complained that her children were lazy and didn’t want to work. She also complained about her husband of 30 years, who was also Hmong.

“He hold me prisoner, want me stay home, cook and clean,” she said. “No let me go outside anywhere, jealous all time.” Tia added, “Now I old, not good for anything anymore, but want to learn new things.”

When I asked her if she smoked marijuana she said she didn’t, but she explained, “I add leaves to boiling water, let cool, put on limbs, take away pains.”

Tia and the Hmong women worked harder than the white guys, though the white guys worked around the clock for two solid weeks to plant and then water by hand 1,200 marijuana starts when it was over 100 degrees.

The guys, who were mostly from Humboldt, drank Lagunitas IPA by the case, smoked cigarettes and marijuana, too. In the evening they barbecued steaks over a grill. I liked them, though I didn’t like it that that they trashed the land. I also disapproved of their use of cocaine, though I didn’t scold them.

Most of them had real skills; they did plumbing, carpentry and electrical work, but they were determined to stay in the marijuana industry. Indeed, the world of marijuana was all they had known for most of their adult lives.

Two of them had grown kids; from what I saw they were good dads.

Late in the season, someone cut through the fence that surrounded the property, and under cover of darkness, stole half a million dollars worth of marijuana. The next morning everyone suspected everyone else. By the time autumn arrived, no one had figured out the identity or identities of the thief or thieves, and the stolen marijuana was never recovered.

This year no one is growing anything on the property, and, though it was cleaned up, it’s now largely covered with chest-high weeds. These days, when I walk there I see wild turkeys and wild rabbits. Yesterday, a Mexican-American guy I’ll call JC showed up to whack weeds. He worked for a week and didn’t finish the job.

“I used to grow marijuana,” JC told me. “I smuggled it to Michigan and made a lot of money. Now, they’re growing pot there and the bottom has fallen out of the market.”

I’m not nostalgic about last summer, but I miss the guys from Humboldt and the women from Laos.

On the day Tia left the plantation and went home, I asked her how she had learned about the pot farm in Sonoma County. “Friend of friend tell me,” she said. “I just helping friends.”

With friends like the Hmong, California marijuana growers are in good hands.

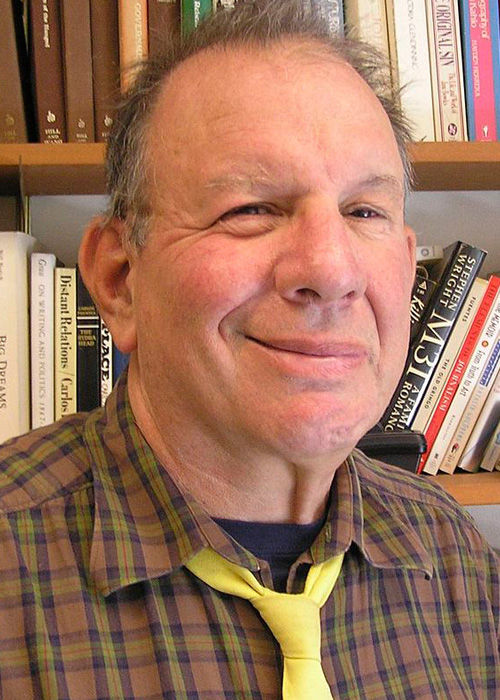

Jonah Raskin, a professor emeritus at Sonoma State University, is the author of Marijuana: Dispatches from an American War, published in French as well as English, and shares story credit for the feature length pot film Homegrown.