It’s the end of the year and time to look back at the 2017 cannabis world in Sonoma County. More marijuana was grown and harvested here than ever before, even after calculating the marijuana lost either directly or indirectly to the October fires. At a large grow site near Kenwood, fire burned greenhouses and marijuana; the owners wasted no time rebuilding and replanting.

One grower, who also works in the wine industry, lost his crop because the police closed the road to his property. When the fires finally died, he drove to his land, but by then the plants had perished because they had not been watered. He also lost the cabernet he was aging in oak barrels; flames burned the barrels and boiled the wine.

More marijuana, plus fewer arrests, meant more marijuana reached medical dispensaries and the black market. Then too, more marijuana than ever before was exported from Sonoma to other places around the country, some of them with no provision for medical marijuana.

This autumn, a pound of marijuana fetched between $2,000 and $3,000 a pound in Georgia; in Sonoma County the price was half that amount.

“The deeper in the Deep South, the higher the price.” That’s a rule of thumb. Dealers shipped as many as 300-400 pounds at a clip and made big money, unless they were caught. That also happened; lawyers came to the rescue.

If more individuals entered the business, others got out. Competition was fierce. It’s not easy to grow top-quality marijuana, much as it isn’t easy to make world-class wine.

I saw beautiful marijuana flowers that a woman had harvested and cured in west county. They were perfectly manicured and they looked like they had been sprinkled with granulated sugar. Not surprisingly, farmers grew marijuana that looked, tasted and smelled exotic. They did almost anything to carve out a niche.

More than ever before, I saw cannabis aficionados smoke concentrates that come in a variety of colors and with names like “wax” and “shatter.” One or two puffs provide a high, though veterans smoke concentrates all day and go about their business without mishap. Now in their mid-30s, they’ve been smoking since they were teenagers.

If more marijuana was cultivated and sold this year, there were also mishaps and worse. On a one-acre plantation, outside Santa Rosa, thieves robbed a few hundred thousand dollars worth of processed marijuana. The field workers assumed that it was an inside job and began to suspect one another, though the owner explained, “I don’t have a clue.” Paranoia goes with the territory.

On a plantation above Cazadero, partners had a falling out. One of them returned, and in broad daylight took what he insisted was his rightful share. Then, he transported it in a U-Haul to a secure, secret location.

Marijuana was definitely a risky business, though it wasn’t the only risky business around, as farmers, viticulturists and ranchers attest.

Because it’s illegal and involves heaps of cash, the industry attracted schemers and crooks as well as dreamers and idealists.

At a plantation near Rohnert Park, I showed up one day and found the field workers sniveling. I thought they had colds. They confessed they’d been snorting cocaine; that was disappointing. But I also met cancer survivors who used cannabis to get off opioids; so marijuana is both a “gateway drug” that leads to really dangerous substances, and also an “exit drug” that helps patients lose addictions.

Unfortunately, there is not yet a reliable test to determine if a driver has a level of marijuana in his or her blood that makes it dangerous to get behind the wheel of a vehicle. Until scientists devise one, there’s a need for designated drivers in situations where marijuana is involved, much as there are designated drivers where alcohol is involved.

Sometimes, growers take the initiative and don’t wait for the government to regulate, reward and punish. Tim Blake is one of them. The founder of the Emerald Cup — the largest marijuana gathering in the world — he has created a prize for those who practice regenerative farming. All too often, in the pursuit of profits, growers cut corners and harm the environment.

“Cannabis can be cultivated in ways that are high-impact, resource-excessive and harmful to people, water and the land,” Blake said. “However, with the right practices, cannabis can also be grown in ways that can help heal the environment.”

The marijuana world still has a long way to go toward that goal. The prize for the best regenerative cannabis farm — which will be awarded at the Sonoma County Fairgrounds on December 10 — is an important step toward the transformation of the industry that will have to take place when adult use of cannabis becomes legal after January 1, 2018, and government imposes standards. If the past has been bumpy, the future promises to be equally so.

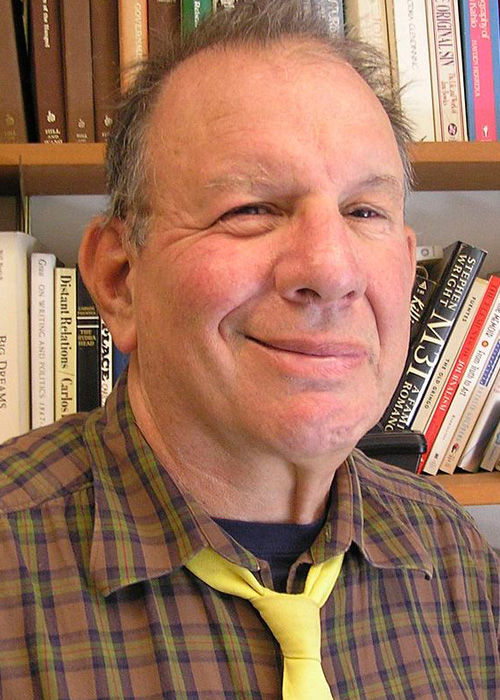

Jonah Raskin, a professor emeritus at Sonoma State University, is the author of Marijuana: Dispatches from an American War, published in French as well as English, and shares story credit for the feature length pot film Homegrown.