ash is near weightless

devouring memories

leaves a heavy heart

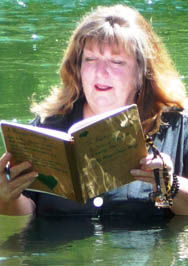

Sitting in the garden, in the crystalline autumn air, after the Great Northern California Fire, I am reading my insurance policy, every sleep inducing word. My friend, Jon Eisenberg, a Healdsburg resident and victim of the Oakland Hills fire, sent me an insurance guide, written by him to inform people who suffered devastating loss in the Sonoma County fires, of things he learned the hard way.

I think of myself as an “I’ll cross that bridge when I come to it” woman, not prone to fretting or fearfulness. But as someone who deals with homes for a living, when it comes to shelter, I take it very seriously — the need of it, the want of it, the loss of it.

And we have been witnessing loss all around. Since I wrote my last column on the heels of Hurricane Harvey, we have been hit with hurricanes Irma and Maria, a mass killing in Las Vegas, an 8.1 earthquake in Mexico, another multiple murder in Baltimore, green berets killed in Niger and numerous international disasters and atrocities I can’t name. These events have been a concentrated, relentless barrage on the heart. But now, the victims have names, we have been inside their homes, and have eaten from their mothers’ china, now turned to ash.

On Tuesday, when the fires had been claiming ground for 36 hours, an advisory evacuation was issued for Fitch Mountain, where I live, and for River’s Bend and Riverview, where my mother and good friend live. Where do you take a 92-year-old non-ambulatory woman and her Fijian caregiver? My sister moved to Windsor two years ago and has a single story home, and thankfully she sheltered all three, with my mother asking “Whose house is this?” for five days.

When I went home I saw that my neighbors had left too. I read the definition of an advisory evacuation: have a bag packed, be ready to go. After the cantankerous behavior of the Tubbs Fire, who could blame people for leaving? Usually the river is our fall back safety plan, but a fire that can leap six lanes of freeway could certainly cross the river.

I couldn’t leave my house, just yet, and, unlike thousands of others, I felt I had a choice about that. My little house needed my energy and vice versa. I drove to Geyserville and out to Alexander Valley. I needed to put my eyes on the fires that threatened us here in Healdsburg before I went to bed. As I drove up 101, I was just in time to see the majesty of the 747 strafe the eastern hills with that glorious red retardant. The most beautiful color in the world. I took this as a sign. I am safe, for now. For now.

In the morning, the smoke was worse, the news was worse. A lot of people in Healdsburg were amazed that that our little town was not the epicenter of the blaze, being vulnerable to wildland fire as we are, on at least three sides. That was the day that my Fitch Mountain neighbor, Omar Perez, called to tell me that the Chalk Hill fire, due east of us, was flaring. He aptly described Fitch Mountain as a roman candle, something all of us who live here know. He said that he and his family would not be spending the night on the mountain and advised me to leave as well.

I thought of all those movies where the stubborn woman stays and gets burned up in a fire, beamed up by aliens or swallowed by a lava flow. I was immensely grateful for Omar’s call, his caring, and yet I decided to double down, to stay another night. His call helped me set my parameters. The first plume of smoke I saw to the east, and I would leave.

I hadn’t packed the first night because somehow I felt, in a spike of superstition, that if I did, I’d have to leave. I can tell you that in my selection process, my pillow was more important than most of my documents. It dawned on me that I owned nothing from my parents. Having moved 37 times, I had foregone sentimentality. I began to see myself as a person without a history, oddly unmoored. All this on my second night at home under the advisory evacuation in a nearly empty neighborhood. I’d wager I might not fare well on a desert island.

What brought me back to my sense of connection was the stories I carry, and the recognition that we are all carrying each other in this way. Everywhere people were talking to each other, engendering shock and sadness, love and faith, joy and relief, our four chambered hearts running on all cylinders.

Candace Williams, a woman in my office, was evacuated from Pocket Canyon with her husband and dog, by Henry One, just as they were about to take shelter in a boat on a pond on the ranch. The call that saved them was made by her daughter, who had lost her home that night.

A broker I was in a transaction with lived in Coffey Park, lost her home in one of the last days of our sale. She got no warning, but she and her husband managed to save their five cats. She went from a homeowner to a potential renter, being serially rejected for having too many beloved pets.

Mila Lamberson, a Healdsburg businesswoman some years back, lost her home in Wikiup, and her art studio. Mila is a renaissance woman, who is an accomplished chef, hair stylist, colorist and artist. She has a very successful line of canvas tie dyed market bags with images on them. Mine has a bee, and my sister has a bicycle. In Calistoga last week, we were in Calmart, and my sister saw a woman whose bag had a travel trailer on it. Jen said “I have a Mila bag too.” And the woman replied “ I lost my home last week, and all I grabbed was this bag and my dogs.”

There can be no denying that in Sonoma County, after the fire, with this terrible wound has come the gift, that our hearts are beating as one.

If you would like a copy of Jon Eisenberg’s fire insurance guide, please email me at on*********@*****st.net and I will send it to you.

Penelope La Montagne is a former Literary Laureate of Healdsburg and is a Realtor at a local real estate brokerage. She can be reached at on*********@*****st.net.