He plied his trade in Sonoma County, committed one of his last robberies here

Author’s note: In addition to interviews, sources for this story include www.blackbart.com, www.sptddog.com, The Cloverdale Historical Society and thewildwest.org.

It was early November of 1883, when several law enforcement officers and investigators from Wells Fargo confronted the dapper man staying in the Webb House in San Francisco. The chap with silver hair and deep-set, piercing blue eyes was dressed in a new suit, carried a natty gold cane and wore a large diamond pinky ring. He looked and acted every inch a gentleman, from his slight English accent to his jovial and gentle demeanor and his unfailing refusal to curse or lose his temper. So complete was his picture as a respectable man, that even his pursuers began to wonder if they had tracked down the right man—for surely this gentle man could not be the infamous stagecoach robber-poet Black Bart.

But, as evidence and witnesses began to pile up against him, the man would eventually confess in quiet tones to his final robbery — the strongbox theft from a Wells Fargo stage in a mountain pass called Funk Hill in Calaveras County, four miles outside of Copperopolis, California. He would spend four years of a six-year sentence in San Quentin, released early for good behavior. On the day of his release, reporters mobbed him to ask if he would be resuming his outlaw ways, to which he replied that those days were behind him. He was then asked if he would compose more poetry, he laughed and is said to have replied, “Now didn’t you hear me say that I am through with crime?”

He would vanish in February of 1888, though he was possibly sighted in Visalia a few days after leaving San Francisco. But his utter disappearance only led to the growth of his legend.

“I have a big crush on Black Bart,” Cloverdale Historical Society Research Library assistant Kay Wells said. “He was a gentleman — he did not use bad language, he never hassled the passengers, he did not rob them. He was a gentleman bandit and bandits fascinate everybody. A lot of them just shot up people right and left but he did not. There were other bandits out there and they were much nastier than Black Bart. ”

In his heyday, Black Bart would ravage the Wells Fargo stages all over Northern California, but he had two particular favorites here in Sonoma County—the Point Arena to Duncan’s Mills stage, which he hit twice in 1877 and 1880 and the Lakeport to Cloverdale stage which he called the “longest 30 miles in the world” and he hit in 1882 and 1883.

Charles E. Bowles was born in Norfolk County, in England in 1829, the seventh child of John and Maria Bowles. He later changed his name to Boles. At the age of two he immigrated with his parents to Alexandria Township in Jefferson County, in upstate New York. He took part in the gold rush, though two of his brothers died while mining. He married Mary Elizabeth Johnson in Illinois and they had four children. He volunteered for the Union Army during the Civil War, was wounded and honorably discharged as a First Sergeant in 1865. He left his family and returned to gold mining, and in 1871 his wife received what she would come to think was a final letter in which he outlined an interaction with Wells Fargo representatives who had driven him from a mine stake. Mary did not hear from him again until after he got out of prison 17 years later and presumed he had died.

This negative interaction with Wells Fargo seems to have spurred his crime spree in to action.

Charles E. Boles, vanished and Charles Bolton, a dapperly dressed man in his mid-fifties, took his place. According to reports, “He stood 5 feet 8 inches tall with clear blue/grey eyes and he sported a brushy moustache. He was a man who liked to live well and intended to do just that. He stayed in fine hotels, ate in the best restaurants and wore the finest clothes. Now all he had to do was find a way to earn a living to support his preferred lifestyle. Ultimately, he would rob 28 Wells Fargo stagecoaches.”

As to why he would chose to focus his skills on Northern California, Wells has a theory.

“Well, I think he just liked Northern California, and why did everybody like it? The Spanish, the Russians, why did they all want to settle here? It was a breadbasket–all the produce that could be grown and the animals here that could be killed–as the Indians figured out long before that,” she said. “And for all those reasons, Wells Fargo was very active in this greater Bay Area, and that’s where the money was. He knew the stages, he knew the routes, and there were so many of them. He never hassled the passengers he just had the driver throw down the box. So I think it’s the nature of the area as to why it was easy to do.”

By all accounts, the name came from a story in the early 1870s called “The Case of Summerfield.” The last villain in the story is dressed in black with unruly black hair, large black beard and wild grey eyes. The character is a certain Bartholomew Graham, also called the “Black Bart,” who is wanted for crimes against humanity and Wells Fargo & Co.

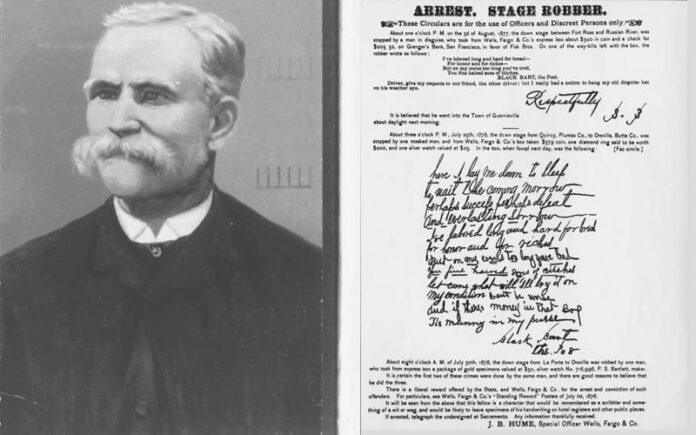

Boles decided to build on this legend. On August 3, 1877 the stage from Point Arena to Duncan’s Mill in Sonoma County was robbed of $300 in coin and a check for $305.52 from the Grangers Bank of San Francisco. A posse looking look for clues found the first poem written on a waybill, under a stone atop a tree stump.

Over the years, part of what built Bart’s legend were the quirks of the character. He wore a flour sack with two eyeholes cut in to it over his head, and wore sacks on his feet to disguise his shoes and footprints. Boles was afraid of horses, so he never rode, and always committed his crimes on foot. He never fired a shot, harmed anyone and never stole from any coach passengers. In fact, after his capture, it was discovered his shotgun had never been loaded. He only left poems at two of his crime scenes, but they only added to the tales of his exploits.

“I think it’s the nature of the man’s personality that everybody attested to as to why he lived on in the imagination,” Wells said. “And the fact that his get up was really funny, with the flour sack over his head. Everybody knew who he was. But for some reasons he thought that was part of his costume. He probably had it for show, ‘I’m here to rob the stage.’”

It is believed he spent time in Guerneville, often stayed at Henry’s Hotel in Fort Ross, and was rumored to have a lady love in Petaluma. After his release from prison, Boles felt hounded by Wells Fargo, seemingly cementing their mutual hatred. They tracked him to the Palace Hotel in Visalia, when he vanished leaving behind a valise with a few odds and ends. Though officially he was enemy number one to Wells Fargo, Wells said she would like to think there was some grudging admiration for the poet bandit.

“I almost think when you read some of this material, that Wells Fargo would shake their heads and smile like ‘he got ‘em again,’” she said with a smile.

Supposedly in 1917, a New York newspaper printed an obituary for a Charles E. Boles, a Civil War veteran. If this was Bart, he would have been 88 years old. However, plenty of rumors abound, including that he is buried in an unmarked grave in one of the old Cloverdale cemeteries.

“That would be great if that were true,” Wells said, though she doubts it is. “He’s our Black Bart, we got him in the end.”

Black Bart continues to live on in local lore throughout all of northern California. Cloverdale celebrated Black Bart days for many years, though that celebration has since vanished like it’s mysterious namesake.

In Windsor, a exhibit at the historical society museum makes an almost wistful connection to the bandit. A diorama from community member Brandon Tynan depicts where a well once sat in the middle of Old Redwood Highway, where travelers would stop to drink.

“It’s reasonable to assume that he stopped there, too,” Tynan said of the infamous road agent.

“He catches everybody’s imagination,” Wells concluded. “He’s kinda local since he robbed all around here. I think he’s great. I love him.”