Smith Robinson Gymnasium named in his honor

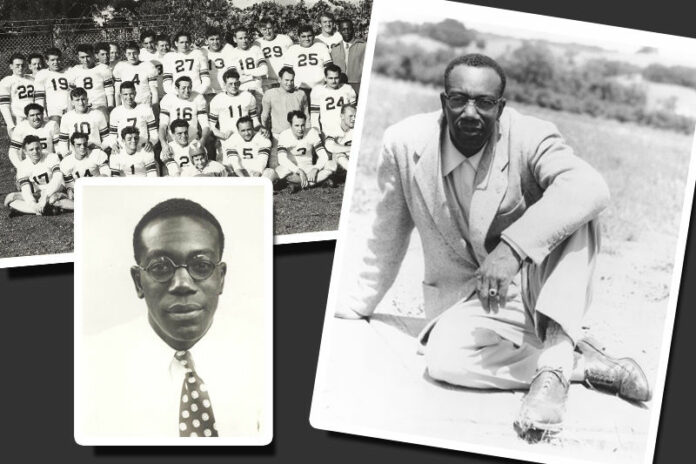

While many Healdsburg residents know that the gymnasium at the high school is called the Smith Robinson Gym, most don’t know why (or who Smith Robinson was; most people think the gym has two last names).

But Smith Robinson was a real person, and an extraordinary one at that, one who turned his personal challenges into benefits for his community and brought support and notoriety to his town.

Smith Robinson was born in Perris, California on November 8, 1907 and came to Healdsburg in 1923, when his father was hired to be the greenskeeper at Tayman Park golf course and the caretaker at Oak Mound cemetery. His father Jesse and his mother Elzora had moved to California from Georgia in search of work, and his sister Effie would be the first African American person born in Healdsburg, according to Holly Hoods, Executive Director and Curator of the Healdsburg Museum.

“Elzora was kind of a mother figure for the whole town,” Hoods said. “She was really active in the church and in her childrens’ lives, but she was also the kind of person that got involved with the high school kids. She’d see someone get bullied and she would stick up for them and make sure they got a little extra attention. The family was extremely well respected, yet also really noticeable because they were the only black family in town.”

“Smitty” as he was known, was a star athlete at Healdsburg High School, proving himself competitive in football, baseball, basketball and track. He was also an active participant in the theater department and active in choir and he held multiple class and student body offices. After a two-year stint at Santa Rosa Junior College where he was a football star, he was accepted to the University of California at Berkeley.

However, he’d been suffering from some dizzy spells, and shortly after arriving at Berkley, the doctors discovered that he had a serious heart defect.

“Basically, he was given six months to live,” Hood said. “It was like, ‘Go back home to Healdsburg and put your affairs in order, and call it a day.’ He didn’t die, but he also couldn’t go to college and couldn’t serve in the military.”

Once World War II was in full swing, the patriotic Smitty tried to contribute to the war effort as best he could. He wrote letters to every active duty service member from Healdsburg, and when the load became overwhelming, he began sending them all a newsletter, called “Smitty’s Scoops” detailing all the Healdsburg happenings.

“This was back in the day when you had to type it on a typewriter and mimeograph it,” Hoods said. “But these people got these newsletters and it made them feel good. I have 10 scrapbooks of people writing him back and you can see how much he meant to people and how much it helped them connect to their hometown.”

The war ended, and back home Smitty continued to hard to help his community. He was known for his skills as a sports coach and mentor, as well as doing things like visiting elderly shut ins and bringing them fresh flowers and food.

He thought female athletes deserved equal recognition, so he started the Smith Robinson Trophy given annually to the outstanding female athlete at the high school. After a student was tragically killed, he launched an early version of Project Graduation, hiring a live orchestra to play in the plaza all night and fixing breakfast for students in the morning.

He worked at Healdsburg Hospital, and led the youth choir at what was then the Federated Church of Healdsburg (it’s now the Community Church). “Back in the day when it was cool to be in a church choir, it was cool to be in Smitty’s choir, Hoods said. “Because it also meant that he was in your life and he paid attention to you and he looked out for you. He was just a really caring adult in the lives of children.”

When the Korean War rolled around, he was again moved by a patriotic notion, following a conversation with a local lieutenant colonel about the demoralized state of his battalion. “(The colonel had written) to his wife and said do you think Healdsburg would be willing to adopt the 1,000 men in his unit. She didn’t know anybody who could do that but Smitty,” Hoods said. “The idea was to become the adoptive hometown, that meant going to the mayor and getting a proclamation at the city council that it would adopt them. It meant writing letters, making candles, making cookies, collecting magazines and it was this total grassroots, community based thing. To me, it’s one of the most heartwarming true stories of Healdsburg history.”

After the war, the battalion repaid the town’s kindness by paying for a playground and other amenities. But the generosity of Smitty’s Healdsburg had caught national attention, and the story was featured by Associated Press and other news organizations. This culminated in an appearance on the TV show “This Is Your Life,” where Smitty was honored for his accomplishments.

“This was back in the day when there were only a handful of TV’s in Healdsburg. They took this guy with a heart condition and they shocked the heck out of him,” Hoods said. “The town kept a secret from him, and meanwhile back at town everybody was gathered around their TVs watching Healdsburg and Smith Robinson get honored for this activity.”

Though he had outlived his doctors’ expectations, on July 15, 1963 Smitty died. On November 10, 1964 the gymnasium at the high school was dedicated in his honor by John Uboldi, Rotary president, with the statement, “Let his selfless efforts in guiding the lives of young men and women of this community remain his everlasting memorial. And let us all be thankful that Smitty passed our way.”

“I would say his legacy in Healdsburg is reflected in the kind of town that we are today,” Hoods said. “When people talk about small town values and what Healdsburg stands for they are talking about Smith Robinson. They are talking about his care for the community and caring for things larger than yourself and wanting to make a contribution to making a strong hometown. I think he still inspires people today. Everyone who knew him, never forgot him and he’s still a part of Healdsburg.”

41.1

F

Healdsburg

November 15, 2024