Green New Deal Town Hall attracts hundreds despite downpour

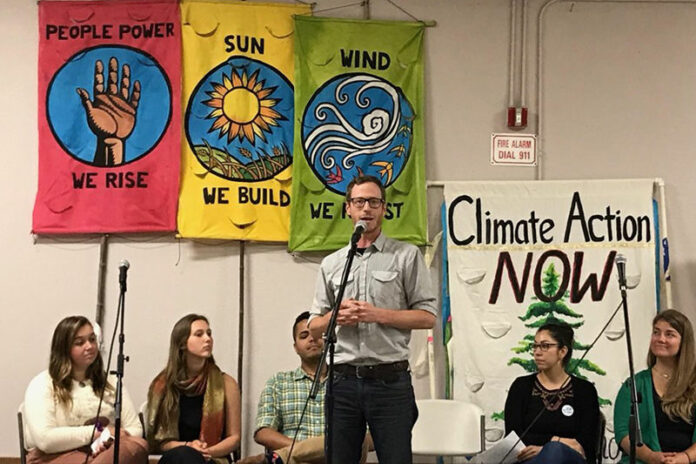

Several hundred people braved the pouring rain Wednesday night to go to the Green New Deal Town Hall at the Sonoma County Fairgrounds, an event which promised to show how the Green New Deal might apply to Sonoma County.

New faces

The evening kicked off with a coterie of fresh young faces, representatives of the Sunrise Movement and Youth Vs. Apocalypse. These groups became famous when members surprised Sen. Dianne Feinstein at her office in February asking her to support the Green New Deal. (She declined, and the way in which she did so exploded all over Twitter.)

Both groups of young activists led the crowd in several songs and talked about how they’d gotten involved in environmental work, the importance of environmental justice and the necessity of supporting the Green New Deal.

“We need to tell our politicians to stand up against climate change or we won’t vote for them,” said Ula Kamastrow, a high school student at Summerfield School.

Kamastrow and the others emphasized the measure’s promotion of high-paying green jobs and the importance of keeping the needs of workers and members of “vulnerable communities” (such as indigenous populations and the poor) front and center during the economic transition to a green economy.

“We know that climate action can create millions of jobs,” said Eleanor Jaffe, a student at Analy High School.

Annabelle Lampson, a high school student at Orchard View School in Sebastopol, told the crowd, “We can make climate justice the No. 1 issue of the 2020 presidential election.”

The word from Washington

Organizers had hoped that North Bay congressmen Jared Huffman and Mike Thompson would make personal appearances at the event, but they were needed in Washington for crucial votes. Instead they sent video messages to the event.

Jared Huffman told the assembled to “think of me and my staff as allies and resources” in the fight against climate change, while Thompson said, “If we don’t act decisively now, nothing else matters.”

Different parts of a big picture

At the main panel discussion, representatives from several local activist organizations gave their particular takes on the Green New Deal.

Who’s to blame?

Professor José Javier Hernández Ayala, the director of the Climate Research Center at Sonoma State University, gave a brief introduction to the science of climate change but saved the majority of his talk for what he called “the social, economic and political actors behind the accumulation of gases in the atmosphere, who are are virtually not explored or as visible in the media.”

“A lot of people benefit from the current economic system and the way it is set up,” he said. “The big fossil fuel companies — the ones that fund our politicians — are the ones who are responsible for the misunderstanding about the science of climate change. They’re trying to create this idea that there are two sides to the issue, when really there is only one scientific understanding.”

The agricultural perspective

Evan Wiig from Community Alliance with Family Farmers reminded the audience that the original New Deal was also in response to an environmental disaster.

“The New Deal was a response to one of the first ecological disasters in our nation’s history: the Dust Bowl. We had an American government and an economic system that encouraged farmers to move west and farm marginal lands with unsustainable practices and the result was we lost about one-sixth of our topsoil. Entire livelihoods, entire towns, entire local economies were totally destroyed. The reason we needed the jobs created by the New Deal wasn’t just the stock market crash of 1929, it was because of unsustainable management of our natural resources and the soil on which our entire civilization depends,” Wiig said. “We are in a similar situation now.”

Wiig pointed out that although agriculture is often seen as a driver of climate change, it could play a major role in turning climate change around.

“Here in Sonoma County we have a number of farmers who are practicing sustainable agriculture. California is the first state in the country recognizing climate change solutions from agriculture and incentivizing farmers to make those transitions. We’re talking about cover crops, crop rotation and a whole suite of practices, some that are new but most of which have been practiced for thousands of years in arid climate.”

Change in agriculture, even with incentives, can be slow, Wiig warned.

“Farmers want to do the right thing, but it has to be economically feasible,” he said. “Farmers do not have it easy and to expect a farmer to turn on a dime and start growing regeneratively grown produce overnight is unrealistic. They need our support — not just government support but support from consumers.”

A just transition

Mara Ventura of North Bay Jobs for Justice emphasized the Green New Deal’s emphasis on workers rights. She laid out a framework that called for a green transition that minimized hardships on workers and emphasized training and apprenticeship programs, which she said “are key to deployment of new technologies” as well as “important roads to the middle class.”

She praised local apprenticeship programs, but slammed most of the developers working in the fire zone.

“Here in Sonoma County it is rare that we have our developments built with local skilled and trained workers, paid a prevailing wage,” she said. “Instead, there is the exploitation of undocumented workers and rampant wage theft happening … Our local officials are not insuring that contractors and developers are protecting workers.”

What are you doing to prevent climate change?

Daisy Pistey-Lyhne, executive director of Sonoma County Conservation Action, asked the assembled crowd to look at what they were personally doing to help solve climate change.

“We’re all a part of this. We all live in homes, drive cars, get around on roads and our impact on the planet is caused by all those components, ” she said.

She reminded the audience that despite its relatively small population, the United States is responsible for 20% of greenhouse gas emissions.

“Our carbon footprint as individuals is way larger than people from other countries because of the way we live.”

“We took this bold step as a county a decade ago and said we’d reduce our emissions by 40% by 2030 and 80% by 2050, but we’re not doing it,” she said, noting that U.S. transportation emissions keep going up, despite strides in other areas such as green building.

Pistey-Lyhne gave a brief shout out to the proliferation of electric cars, but ultimately called for more public transit and a different type of residential development that was denser and taller than most people in Sonoma County have traditionally been used to.

“As much as we’re afraid of building up, we need to build up,” she said, noting that everyone on the panel was under 40 and none of them owned their own homes, basically, she implied, because of ongoing opposition to denser development.

“We need to support development in our city centers and in our neighborhoods and stop building single family home developments. We have enough of those,” she said, especially with a graying population that is looking at downsizing and a younger population looking at getting a foothold in the housing market.

“Although it’s counterintuitive,” she said, “denser developments are more climate friendly, especially when they’re combined with transit.”

Work on your own town

Before the event ended, the organizers asked participants to go and meet with the people from their towns who were working to get their local city councils to adopt local versions of the Green New Deal’s Climate Emergency Resolution. Around the room, local activists held up clipboards with the name of their towns.

James Freed of Sebastopol was gathering signatures and looking for members for Sebastopol Climate Action, a citizen group that is lobbying the city council to adopt a version of the Green New Deal Climate Emergency Resolution.

“We’re meeting one on one with city councilmembers, and we hope to put together and outline for a resolution they can get behind,” Freed said.

Further north, Tyra Benoit and Dr. John Mihalik were trying to do the same thing for Healdsburg.

“We both live in Healdsburg, but we actually met for the first time in Atlanta at the Climate Reality Training in March,” Benoit said. “We’re hoping to approach the city council of Healdsburg with a Climate Emergency Resolution. Right now, we’re just trying to make connections and bring other people into the process.”

Terry Taylor held up a sign for Windsor.

“We’re going to try and get the town council to reflect on and hopefully pass the Climate Emergency Resolution,” he said. “Then we’ll look at what actions the town can take to really implement that for the township itself. We’re also trying to get the citizenry to grow their awareness and to get involved and engaged in the biggest crisis of our time.”

50.7

F

Healdsburg

April 19, 2025