At the age of 22, I didn’t drink alcohol or smoke marijuana, either. I didn’t know anything about pot, though I assumed it was a dangerous drug that would damage my brain. As a student I didn’t want to fry my precious brain cells.

Fifty-three years later, I consume Pinot and pot in modest amounts. I don’t get “wasted” or even intoxicated. In some ways, I’m still the cautious fellow I was at 22.

Today’s twenty-something-years-olds are dramatically different than the generation into which I was born. That’s especially true in northern California where there’s an abundance of first class wine and first class marijuana. Nowadays, teenagers grow up with pot and Pinot; they use weed and consume wine in high school, at college and when they go to work nine to five. They’re the norm, not the exception and they boast about their habits on Facebook and Instagram. Earlier generations often outgrew their cannabis habits. In their view joints were kid stuff.

Twenty-two-year-old Noah Gibbons belongs to a generation that has rarely if ever thought of marijuana as a criminal, an immoral or a harmful substance. “All my friends came of age with legal medical marijuana,” he told me. “We never really experienced the pot prohibition that impacted my father and his friends.”

Gibbons began to smoke weed at the age of 18. Four years later, he’s still smoking it, as I learned at Handline, the seafood restaurant in Sebastopol. At the end of our conversation he asked me to please not use his real name. He’s about to join a new dispensary in Sonoma County — if everything goes according to plan — and he wanted to preserve a modicum of privacy before he goes public about his pot connection. The cost to open the dispensary where he’ll be part of the team: $1.5 million.

“I like wine and I like weed,” Noah told me. “They’re both a big part of my life. Most of the people I know use both and I think that’s normal for my age group.”

Noah grew up in San Francisco and attended an elite high school in the Haight-Ashbury. “The school slogan was ‘Just Say Know,’” he explained. “The teachers understood that Nancy Reagan’s ‘Just Say No’ was unreasonable and wouldn’t work. Our teachers wanted us to pursue knowledge wherever it took us and learn from our experiences.”

Noah’s father — a high profile lawyer — also encouraged his son to venture beyond narrow confines. Accordingly, he has taken advantage of almost every opportunity that has come his way. “As soon as I turned 18, I got my medical marijuana card,” he said. “I went to a dispensary just two minutes from my school and bought weed.”

After high school, he attended a private college in the East, but he developed back pain and was forced to return to California where an osteopath put him on the road to wellness. Noah has not returned to college, but he has continued his education. No 20-something year-old is more devoted than he to the study of marijuana. When the dispensary opens this fall he’ll have a lot to offer patients and coworkers.

Then, too, no one I know has traveled more widely to pursue his studies. He’s roamed from Silicon Valley to the Central Valley and from Portland, Oregon to California’s north coast.

“I have one foot planted in the marijuana fields and another foot played firmly in the world of venture capitalism,” he told. “I’m happy as a clam.”

In the course of his studies, he’s met farmers who are crossbreeding marijuana strains and developing new potent seeds. He’s visited medical marijuana dispensaries all over northern California, and he’s met legendary marijuana activists, including Dennis Peron, who spearheaded the campaign for medical marijuana. For six months, Noah worked for a Santa Rosa company that tests marijuana for potency and for molds and pesticides.

Almost everywhere he’s traveled he has seen the big marijuana guys get bigger, while the little marijuana guys have struggled to survive. He’s also pleasantly surprised that marijuana has made deep inroads into suburbia and the world of high finance.

“I recently met a woman — a baby boomer — who created a cannabis club just for women her own age,” he told me. “They meet to smoke weed and talk about it.” Noah added, “I also made the acquaintance of a guy who has been a banker in Hong Kong and Singapore and who is a regular user.”

At the top of his list of favorite places, there’s “Wonderland,” a huge, thriving marijuana business in Garberville that sells thousands of different strains and where business is always brisk. “I was at the nursery one day when these Russian guys pulled up in a humungous truck and filled it with hundreds of clones,” he said. “It was an amazing spectacle to watch.”

Also on his top 10 list: San Francisco’s “Barbary Coast,” which he calls an “Amsterdam-style marijuana café.” Barbary Coast, at 952 Mission Street, offers a vast array of marijuana strains; the surroundings are luxurious. Perhaps the most interesting person Noah has met is a young man we’ll call “Roderick,” who grew up in Afghanistan — where his father was a diplomat — and who smuggled rare Afghani seeds into the U.S.A.

What to make of Noah Gibbons and his generation? In part only time will tell. Still, it’s clear that they’re as devoted to cannabis as the idealistic hippies of the 1960s and 1970s, though they have their own rituals and rites and their myths and legends.

“There are folks who still have the outlaw mentality and don’t care about water and soil,” Noah told me. “I don’t think they’ll survive for long in the new world of legal recreational marijuana. The people who embrace permaculture and biodynamic farming and who are mindful of brands and strains will be the survivors.”

Perhaps someone in higher education ought to review Noah’s credentials and issue him an honorary degree in the art and science of cannabis. For a young man without a B.A. he’s come a long way and he’s still going strong.

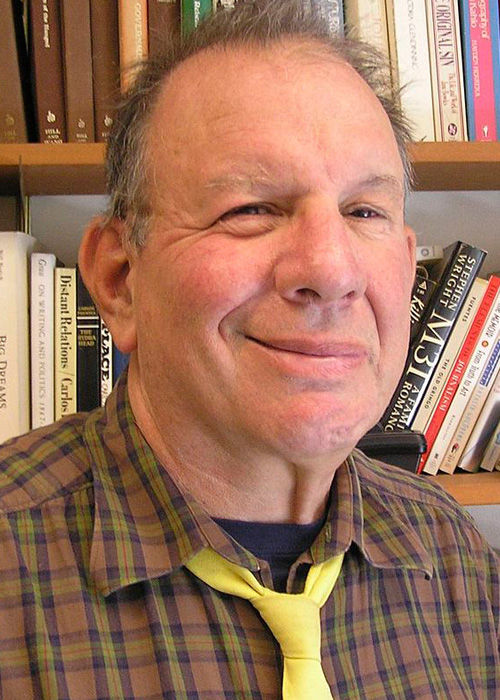

Jonah Raskin, a professor emeritus at Sonoma State University, is the author of Marijuanaland, Dispatches from an American War, published in French as well as English, and shares story credit for the feature length pot film Homegrown.